Established in 1575, the Bols Distillery in Amsterdam, Holland remains the world’s oldest surviving distilled spirits brand, producing juniper spirits for almost 350 years.

Related Stories

Part 1: The History of Gin – Conflict and Decadence

Part 2: The History of Gin – The Boom and Drunken Bust

Part 3: The History of Gin – From Debauchery to Modern Day Decadence

Born in 1652 during a golden age in which the Netherlands exploded in technological, economic and military advancement – a young Lucas Bols would become responsible for evolving his family name into a brand synonymous with sailors and colonists everywhere. At the heart of this success lay his 1679 investment into one of the most powerful organisations in Europe’s history, the Dutch East India Company (or “V.O.C.” – Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie). Governed by a group of shareholders known as Heeren XVII (“Masters Seventeen”), Lucas’s new association allowed him to become the exclusive supplier of “fine waters” to the company, their merchant vessels and holdings in both the East (Indonesia) and West (Caribbean) Indies. Using his newly acquired influence and resources, Bols collected fruit, herbs and spices from throughout the traded colonies using them in many new products – such as the popular Orange Curacao.

Genever – The Official Spirit of The Netherlands

After reaching its peak during the mid 19th century, genever lost much of its reputation and recognition after mass production methods influenced the spirits traditional quality. One of the major influences in the drop in popularity of genever was an invention which many years later would inadvertently save rival English gins from their ruinous reputation.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Cellier Blumenthal published the first patent for a continuous Column Still in 1813. With distillation up to this time utilizing the much slower and labor intensive pot still, Blumenthal’s invention would give the world the first process for the mass production of high alcohol compounds. Initially built around a single column, the still allowed the fermented mash (barley beer) to be continually added to the still during operation keeping a constant outflow of distillate instead of the batch processing needed in a pot still. Today the Column Still is also known as the Coffey Still after Irishman Aeneus Coffey patented and popularize an improved version of Blumenthal’s design. Blumenthal’s invention caught the attention of the King of Belgium, Leopold I, who convinced him to promote both his still and the use of nationally grown sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) in replacement of the traditional and expensive barley. As such, many genever took on a new flavor ill enjoyed by general consumers.

Genever Regaining its Pedigree

Today however genever has regained much of their distilling pedigree and are once again producing spirits of outstanding quality. In recognition of this, the category was rewarded an AOC (Appellation ‘d’Origine Controlee) in 2008 which safe guards the quality standards of all locally produced genever in the provinces which defined the Low Countries of their heritage. In essence the category is defined by five core styles;

- Genever (Jenever): A juniper flavored spirit with a minimum of 30% ABV (60 proof) by blending of neutral alcohol and malt wine

- Grain Genever (Graanjenever): A genever distilled from 100% grain

- Old Genever (Oude Jenever): Genever containing a minimum of 15% malt wine

- Young Genever (Jonge Jenever): Genever containing a maximum of 15% malt wine

- Fruit Genever (Fruit Jenever): Young genever infused with fruit

Click image to enlarge.

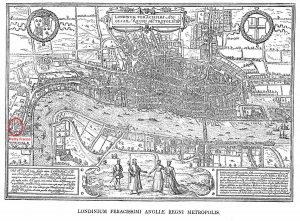

While both The Netherlands and modern-day Belgium were fighting to hold the Spanish Hapsburgs at bay during the Dutch War of Independence (1568–1648), England had already been producing juniper spirits as early as 1572 from what were called Strong Water Shops – the first commercial liquor retailers. The earliest shop on record belongs to the aptly named Aqua Vitae House (“water of life”) located between two popular taverns, the Ram’s Head and Mother Mampudding’s, near Petty Wales and the Tower of London. These new establishments helped transform social drinking habits away from low alcohol beverages such as wine and ale into high alcohol distillates, all generically referred to as brandy from the dutch term for “burnt wine” – brandewijn. Up to this point, Londoners only imbibed distillates in the form of rudimentary tonics and tinctures produced by groups such as the Worshipful Company of Barbers, where patrons could receive a haircut, some bloodletting and a spirituous dram, all in the one sitting. Quality.

The Birth of the Modern Bar

A mere five years after the establishment of the WCD, spirits were produced in volume enough for the House of Lords to impose England’s first tax on imported and locally produced spirits. With the introduction to coffee house society after the opening of the first European café in Oxford in 1651, England experiences an awakening of the modern bar as a spirituous domain for social and intellectual engagement. That said, it is still an engagement built around a society well learned in the practice of intoxication.

Gin Takes a Dive

Gin’s sudden and absolute plunge from the enlightened coffee houses and private rendezvous of the elite to the slums of St Giles, falls somewhat unfairly on the shoulders of one man – William III of Orange (Prince of the Dutch Republic). William or King Billy as he was known by the Scots and Irish, ascended the throne of England in 1689 becoming King and joint monarch (alongside his native bride Queen Mary II) thanks to a parliamentary coup known as the Bloodless or Glorious Revolution. That same year one of England’s most important constitutional documents would be passed – the Bill of Rights – opening up freedom of speech and limiting the powers of the sovereign monarchy. Unfortunately for William, he would be better remembered for what happened next.

Higher Taxes on Imports

William III began his reign by imposing high taxes on the import of many luxury foreign goods while banning French brandy outright as it represented his lifelong enemy King Luis XIV not to mention the previously deposed monarch and Catholic sympathizer, James II. Primary to the Williams plan lay tax benefits for local English subjects to distill their own spirits from, “good English corn” in an attempt to increase the sale of national produce. It is also argued that while on paper Williams legislation offered opportunity for economic growth, many of the Members of Parliament who helped orchestrate the coup placing William on the throne, were also the landlords for many of the farms which produced the nations corn and wheat.

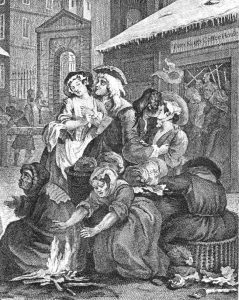

The Distillers Act of 1690

The second major error came with the passing of the Bank of England Act in 1694 which raised the duties and taxes imposed on the production of beer, ale and the other liquors under the pretense of supporting the war against France. The effects of which made fortified gin cheaper to buy by volume than common beer. The implementation of the Distillers Act also came about at a time when London was at one of it’s most impoverished in history with a supposed one in ten families living below the bread line. Add to this, the terrible levels of hygiene, quality of drinking water and the Great Winter of 1739 in which the Thames froze over halting major trade for three months – and gin became the place to turn. As a distilled spirit it was healthier (at least from bacteria), cheaper and easier to acquire than clean water and a mental barrier against the cold.

A Quarter of London’s Residents Employed in Gin Production

A Poison Capable of Rendering it’s Users Blind, Crippled or Dead

The Gin Act of 1736

Gin consumption finally began to decline after the passing of the Gin Act of 1736 – it was the eighth attempted act to do so. Key to its success were a series of controls on the production and retail of spirits, an increase in excise on taxes and importantly supplying the manpower to enforce both. The Gin Craze did however see women and men drinking in bars side by side for the first time, unfortunately their children were often also alongside them, equally drinking, equally drunk and equally addicted. It was estimated that 9000 children in London alone died of alcohol poisoning this same year.

Saved by the Bell (Inside the Coffin)

With so much starvation, poverty and drunken excess, the popular gin shop phrase was,

“Drunk for a penny, Dead drunk for twopence, Clean straw for nothing”.

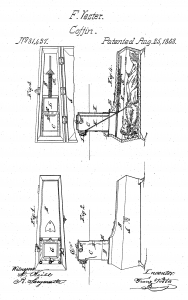

It became all too real with some shops reserving a straw lined room out back to store the bodies of patrons when they pass out. Whether they awoke again was only a matter of time. The phrase “saved by the bell” is believed to be descended from this period when many of the public became so paranoid about being buried alive after a big drinking session that they would write the use of Safety Coffins into their wills. These coffins utilized a bell or observation device to draw the attention of a cemetery night-watchmen should a buried body awake from a merely long intoxicated coma. Click the coffin image below to see it full size.

Click image to enlarge.

It is also commonly believed that the practice of a 24 hour “wake” before burial also stems from this same period of paranoia although there is little to substantiate this. Fear of being buried alive became so common after the gin craze that many safety coffin designs were submitted for patents and continued throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The earliest on record was for Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick before his death in 1792. Laid to rest inside a tomb, the Dukes coffin involved a window for light, a tube supplying air into the box and a latch operable from the inside via pocketed keys for both the coffin and tomb.

Dr. Adolf Gutsmuth believed in his patent so much he buried himself alive more than once in demonstration of his 1822 design during which he enjoyed a meal of soup, sausages and even ale delivered to him through the coffin’s feeding tube. A further patent in 1829 by Dr Johann Gottfried Taberger, involved a system of strings attached to the limbs and head of the deceased leading to a bell housing which would ring to alert the night-watchman who in turn would insert a bellows and pump air into the coffin until further help could arrive. The problem with dead bodies is their tendency to swell during decomposition and therefore often moving in their place. As such, more than one false ringing was made albeit scaring the hell out of whoever was on shift at the time, let alone the experience of exhuming a bloated and semi decomposed coffin in mock rescue.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Like us on Facebook and Follow us on Twitter.

References

- Gin: A Global History, Lesley Jacobs Solmonson, 2012

- Gin: The Much Lamented Death of Madam Geneva

- Distillerie deBiercée

- Nationaal Jevevermuseum Hasselt

- Genever: Belgium’s Traditional Spirit for Over 500 Years

- Project Gutenberg –The Works of William Hogarth: In a Series of Engravings With Descriptions, and a Comment on Their Moral Tendency, Rev John Trusler – 1833 (page 67)

- Internet Archive –Heads of the People: Portraits of the English, Kenny Meadows and writers – 1840

- The Worshipful Company of Distillers

- British History Online –Statutes of the Realm: volume 6: 1685-94

- Bank of England Act 1694

- London Online:The Winter of 1739-40

- Google Patents:Improved Burial-Case [US 81437 A], Franz Vestee – 1868