The Sazerac Cocktail in all its Understated Glory

Requiring an average ritual of around 5 minutes to make per drink (depending of who you ask), it’s a wonder that in a world dominated by the ten-second VFC (Vodka Fruity Cocktail), this drink should be recognized at all? Yet as with most great legends, the truth is often well insulated behind layers of rumor and hearsay. Layers which as bartenders, we’re all a little responsible for spreading. To debunk a big one early on; the Sazerac is NOT the birthplace of the word ‘cocktail’ despite a great story linking a French snifter with the name. Sorry kids but the dates just don’t match, as you’ll see later.

So in an effort to further unravel the true story behind the Official Cocktail of New Orleans and an icon of mixology, there’s only one place to start; with a young man named Antoine Amedee Peychaud.

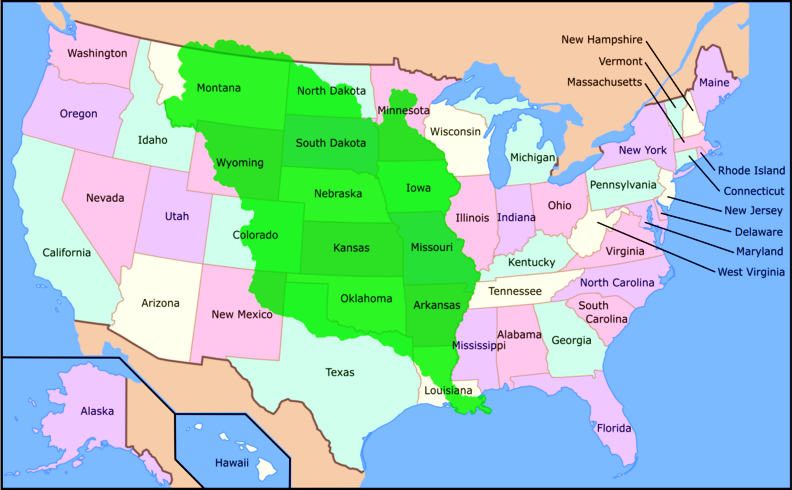

Peychaud’s Bitters

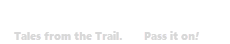

Having established their colored independence from Napoleonic French rule in 1804, the newly named Haiti (formerly Saint-Domingue) became the only slave revolt in history which led to the founding of a new nation. As a consequence of the revolution, large numbers of French colonials migrated throughout the Americas escaping violence and economic collapse.

Haiti Revolt. Taken from the Burning of the Plaine du Cap by Martinet + Masson, 1833.

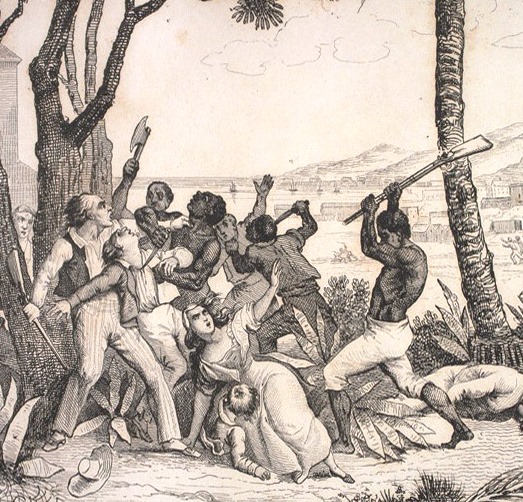

Up until the year previous, an entire third of the United States from New Orleans in the south stretching all the way north to the Canadian border, was also a French territory under the rule of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Named Louisiana after French monarch King Louis XIV, the land mass was part of the dream of a new Napoleonic America built on the wealth of sugar cane plantations from French Caribbean islands such as Saint-Domingue. Plans which were well scuppered after the loss of the island to revolt. As a result of the economic loss made from both his holdings on the island and his attempts to quash the uprising, the land of Louisiana along with its capital city Nouvelle-Orléans, was sold by Napoleon to a young United States for 60 million Francs (approximately USD$15 million today). An event remembered today as the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

Related

How to Make a Sazerac Cocktail – The Official Drink of NOLA

By 1809 nearly 10,000 French refugees were reported to have emigrated from Haiti into New Orleans escaping persecution. The number almost doubled the city’s population in one year, bringing with it a rebirth of French creole food, music and culture still evident today.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Map showing the extent of the territory of French Louisiana when sold in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Three years later in 1812, Louisiana (now a much smaller region) was granted an official state of the United States with a further three years after that, seeing Napoleon Bonaparte passing his final years on his island prison of St Helena after losing to the English at the Battle of Waterloo.

Why is this relevant? At some point during this period, a young man named Antoine Amedee Peychaud arrived into New Orleans, along with the masses of Saint-Domingue refugees, in search of a new future. Today, this same man is remembered as the creator of the self entitled Peychaud’s Bitters from which evolved our said cocktail – the Sazerac. While the exact birth details of Msr Peychaud have been difficult to obtain, thanks to the support of modern genealogy platforms such as Ancestry.com, much of his family tree which can be traced back to French Saint-Dominque.

A Modern Day Bottle of Peychaud’s Aromatic Cocktail Bitters.

In a world full of drinks bloggers as guilty as I, there are a host of online timelines and articles which claim to trace the story of Antoine Peychaud. Some place his birth in New Orleans at the end of the 18th century or how he was born to a father by the same name and ex Inspector General for the State of Louisiana. While I have not been able to discover evidence of either, it is recorded that New Orleans apothecary Antoine Amedee Peychaud, died on 30th June, 1883 at 80 years of age. Thanks to this death certificate we can place his date of birth at circa 1803.

Tracing his life back from there we know that he had three children with his first wife Celestine Cruzat (Emile Antoine, Jean Amedee and Octave Antoine) and a further son (George Peychaud) with his second wife Amelie Laffenard after the passing of Celestine in 1854. Peychaud’s listed parents (Charles Louis Peychaud & Rosaline Martinet Peychaud) are believed to have been wealthy coffee plantation owners from Bordeaux, France but evidence is yet to be uncovered.

When looking through immigration records for any A. A. Peychaud arriving into New Orleans around the early 1800’s, no direct link is found despite no shortage of Peychauds arriving out of Santiago, Cuba (a common port of change for refugees from Haiti). With so many French immigrants arriving into the city over this period it is difficult to accurately trace a single passenger with certainty. The name Peychaud itself was common enough as shown in a New Orleans business directory from 1861 were a listed nine Peychaud’s were operating businesses from tailors to accountants and insurance brokers – not to forget one “Peychaud, Antoine A. ‘druggists’ residing at 90 Royal Street, Latin Quarter”.

Regardless of when he arrived, the aforementioned druggist Antoine Peychaud, went on to create an aromatic bitter of historic influence. According to the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum, in 1841 Peychaud set up his own shop called Pharmacie Peychaud where he became well known for dispensing a patented aniseed and gentian rich herbal remedy named Peychaud’s Bitters. According to Old New Orleans, a History of the Vieux Carre, Its Ancient and Historical Buildings by Stanley Arthur (1936), Peychaud was also a masonic figure of note holding titles of ‘Worshipful Master of the Concorde Blue Lodge’, ‘Grand Orator of the Grand Lodge’ and ‘High Priest of the Royal Arch’ which he used to help spread the popularity of his bitters by hosting masonic drinks at his pharmacy.

And work it did. Today Peychaud’s is the second most sold bitters in the United States and a must have ingredient for the world’s top cocktail bars. But it wouldn’t be until the emergence of a new drinking trend that Peychaud’s name would be known outside the state. Enter the cocktail.

Toddy’s vs Cocktails

During the 1840’s, Antoine Peychaud prescribed and dispensed his patented herbal bitters as a rudimentary toddy mixed with water, sugar and French brandy to relieve the ails of all his clients irrespective of malady.

Traditional French aluminium “coquetier” cup.

The mixture would arrive in a traditional French egg cup shaped vessel known as a coquetier. Legend continues that to his colonial customers the mixture became well known by this name – a fact well endorsed as the birth of the term cocktail. In reality, while a great yarn, there are references aplenty to the existence of the word “cocktail” well before Antoine was even born [See – Cocktail: History behind the name]. Regardless, this was a cocktail in the purist sense and all that Peychaud lacked was a means to bring it to the masses. His dream would be realized thanks to the timely era of the coffee house.

By early to mid 19th century America, the coffee house era was reaching its peak, redefining the modern drinking establishment from the spit-n-sawdust rum fueled taverns of old to venues of intellectual banter and social prestige. So vital was the role of the coffee house on early American society that in 1776, the Merchants Coffee House of Philadelphia was selected as the first location to publically announce the United States Declaration of Independence. By 1840, the importance of the coffee house had little diminished however the emergence of the cocktail, cobbler, toddy, flip, sling, swizzle, sour and punch had somewhat taken over popularity of the more caffeinated libations. With word spreading of his pharmaceutical brandy-cocktail, many local coffee houses began recreating Peychaud’s miracle tonic to their aspiring patrons and not always using the man’s bitters.

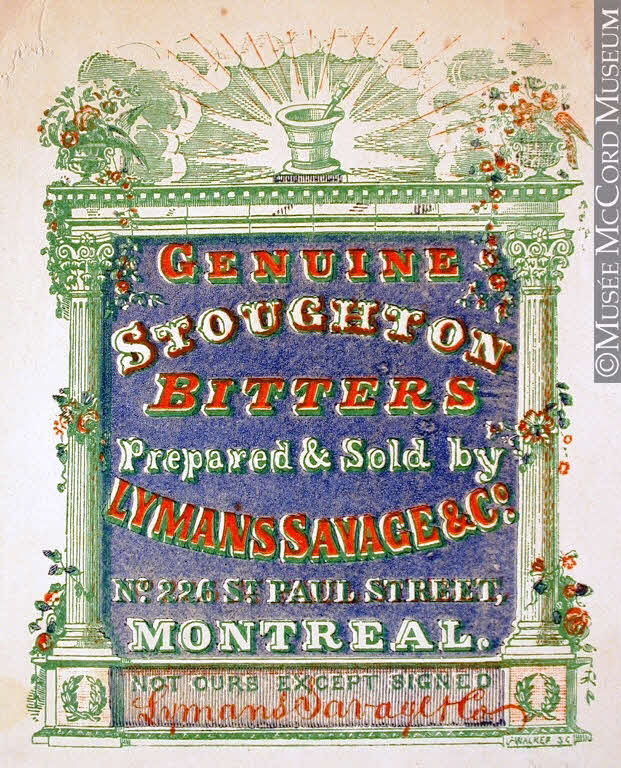

Engraving “Genuine Stoughton Bitters”, Lymans Savage + Co. [M930.50.7.153] – c/o McCord Museum.

“A brandy-toddy is made by adding a little sugar, a little water and a great deal of brandy – mix well and drink. A brandy-cocktail is composed of the same ingredients with the addition of a shade of Stoughton’s bitters – so the bitters draw the line of demarcation”.

Clearly, Peychaud was not the only player and most likely not the first to mix his bitters through a brandy-toddy. Brandy had always been believed to hold medicinal properties and as such was commonly dispensed throughout colonial apothecaries and chemists. As for Stoughton’s Bitters, they were listed as having been created by Thomas Walsh of 99 Tchoupitoulas Street in the American Quarter of New Orleans. While this is undoubtedly true, the original Stoughton’s Bitters was the elixir that started it all having been patented in England way back in 1712 and introduced into America with the first colonists. Stoughton’s – while originally on a scale to easily rival that of Peychaud’s – made the mistake of publishing his recipe early on which led to a large number of copycats and fakes released onto the market. A reaction which ultimately ended the brand. Thomas Walsh’s New Orleans bitters was no doubt one of these.

Meanwhile Peychaud had undoubtedly his own share of dispensing coffee houses, but before he could establish his role in cocktail infamy, he needed a champion and found one in a man named Sewell Taylor.

The Sazerac Coffee House

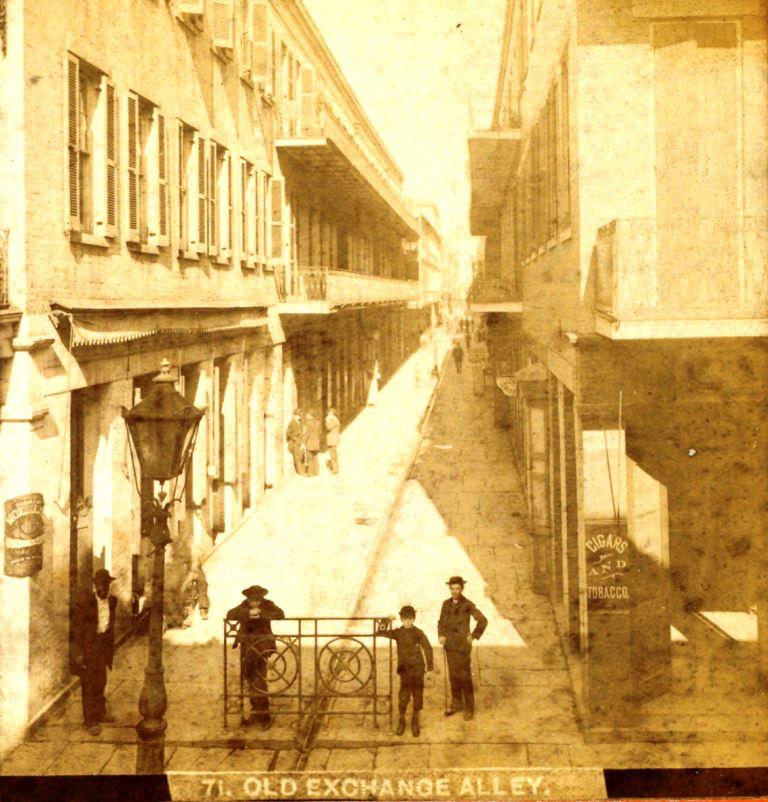

Old Exchange Alley by George F. Mugnier circa 1870.

While Peychaud was selling reasonable qualities of his bitters to consumers and publicans alike, the use of his bitters in the now popular brandy-cocktail, was only requested by name in a few of the cities establishments. That all changed circa 1840 when Sewell Taylor established the Merchants Exchange Coffee House at 15-17 Royal Street (or 13 Exchange Alley via a back entrance), located just down the road from Peychaud’s own dispensing chemist.

The Merchants Exchange (aka Exchange Coffee House) was one of the largest coffee houses in New Orleans and quickly became one of the most popular. As a skilled merchant himself, Taylor was the sole importer for a number of products which he sold over the counter at the Merchants Exchange. One such product was a French brandy made in Limoges, France (just east of Cognac) called Sazerac-de-Forge et Fils. Around 1850, Taylor handed the day-to-day operation of the coffee house over to Aaron Bird and opened a liquor store selling his imported products across the road at 16 Royal Street. It was here that he hired a young Thomas H. Handy as a shop clerk. By this time Taylor’s imported Limoges brandy-cocktail, was creating a reputation amongst its regular punters. Unlike other establishments, the Merchants Exchange only used Sazerac brandy and Peychaud’s bitters in their cocktail. To further promote the popularity of their serve, circa 1852 Bird ingeniously renamed his venue the Sazerac Coffee House – and a legend was born.

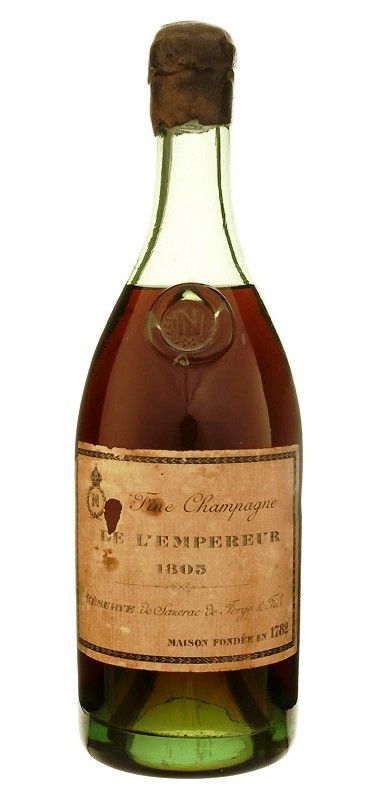

Sazerac-de-Forge et Fils, Vintage 1805. For sale at BrandyClassic.com for £12,888.00.

Even today the Sazerac Coffee House is well remembered for stories of its 125 foot long bar behind which could be seen around 12 bartenders doing little but mixing Sazerac cocktails at any one time. The original site of the coffee house can still be found on Royal Street today thanks to a white tile lettered with the word “Sazerac” to mark the spot.

By the start of 1860, Bird handed the business over to John B. Schiller who ran it until 1869 when Taylor’s now experienced clerk Thomas H. Handy stepped away from the liquor store opposite to take control of the Sazerac Coffee House for himself.

Throughout this whole period, Peychaud and his bitters has become a New Orleans brand recognised against that of the Sazerac cocktail and French brandy by the same name. His close relationship with Taylor and Handy becomes evident when circa 1870, Peychaud closes his apothecary store for good and enters into business with his new partner Handy. By 1871, the new Thomas Handy Co. is both the sole importer of Sazerac brandy and manufacturer of Peychaud’s Bitters creating in one move, a monopoly on New Orleans favourite drink. But the victory was to be short lived as the 1870’s also hails the emergence of a European pestilence which would single handedly alter the drinking habit of the modern world forever – Phylloxera.

Phylloxera Epidemic

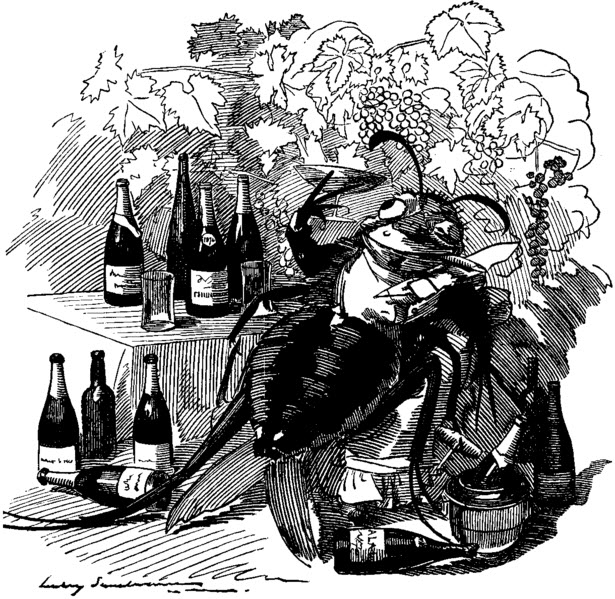

The Phylloxera aphid captured as per it’s reputation of consuming only the finest of grape stock. Punch c.1890.

Originally known by the name Phylloxera vastatrix, this near microscopic vine-louse (more accurately an aphid) was singly responsible for wiping out the vast majority of all grapevines in Europe during the late 19th century.

Arriving via ship into English ports from its home in North America circa 1850, by the following decade it had made its way into the Languedoc and Southern Rhône regions of France where the real damage began. By 1890 it was estimated that around 2/3 of all European vineyards were infested or destroyed. Endemic to the North Americas, Phylloxera lives in relative harmony with their local vine stocks after the continents local grape vines had evolving to resist the aphids infestation. Desperate attempts to stave off the spread of Phylloxera saw farmers try everything from chemicals to flooding vineyards, spraying goat urine or event burying live toads. A tradition still seen today is to plant roses at the head of grape vines as an early warning system since roses show signs of infestation or damage long before that of vines.

With the financial impact of Phylloxera hitting the French economy almost as hard as the farmers, the government offered a prize of over 320,000 Francs as a reward to anyone who could produce a curative solution. In the end the only action was not a cure but a preventative. By the means of either crossbreeding hybrids of American and European vines or more commonly, grafting American root-stock onto old European varieties, further outbreaks have been averted.

Sazerac Straight Rye Whiskey.

Unsurprisingly, with a grape industry completely reset in the shadow of such an outbreak, supply of wine and wine based products dropped or stopped completely throughout European colonies and merchant nations, and that included America. The event might have rated higher on their merchants coffers if they weren’t already busy recovering from Civil War (1861-65). What little could be spent on international trade was not allocated to the importation of brandy. Whiskey had been produced in America since the first settlers but was rarely seen as a spirit of the gentry until supply of French brandy died up. In England, the same was happening with Celtic whisky which was equally introduced to a new demographic of premium consumers off the back of a drop in the supply of brandy.

The late 19th century would also see three further influential events in the Sazerac story; the closing of the Sazerac-de-Forge et Fils brandy company in France (c.1880), the death of Antoine Peychaud (1883) and the death of Thomas H. Handy (1893). Prior to the passing of Handy, his company began to produce and market the Sazerac cocktail in a pre mixed bottle ready-to-drink but it was not to take off. With the signature brandy no longer obtainable and tastes swinging towards American whiskey, Handy’s former secretary C. J. O’Reilly purchased the rights to Handy’s business relaunching the charter as the Sazerac Company and launching an American whiskey by the same name. As the 20th century dawned, so did the modern cocktail. Whiskey was now regarded a viable spirit for cocktails and as such had almost completely replaced the brandy serve in the most classic recipes [see: Juleps, Planters and 400 Years of Suckers].

The Worlds Drinks and How to Mix Them by William T. Boothby, 1908 – c/o MetaGrrrl.

The Sazerac cocktail would finally see its first press in 1908 when appearing in The World’s Drinks and How to Mix Them by William T. Boothby (aka “Cocktail Bill”). Boothby’s recipe shows the transition from French brandy to American whiskey calling for a measure of “good whiskey” in his serve. It is said that Handy passed his recipe for the Sazerac to Boothby directly prior to his death. Since Boothby was a successful bartender based out of California and San Francisco, we can only presume it was gifted during a visit to the creole South although it does seem strange that Boothby’s recipe called for the use of Selner’s bitters instead of Peychaud’s. A major change to a recipe supposedly given in person by the then owner of Peychaud’s bitters.

At some point during this period, one further ingredient was added to the modern Sazerac serve and while not part of the original recipe, it is the primary element which separates this cocktail from that other popular classic, the Old Fashioned.

The Absinthe Conundrum

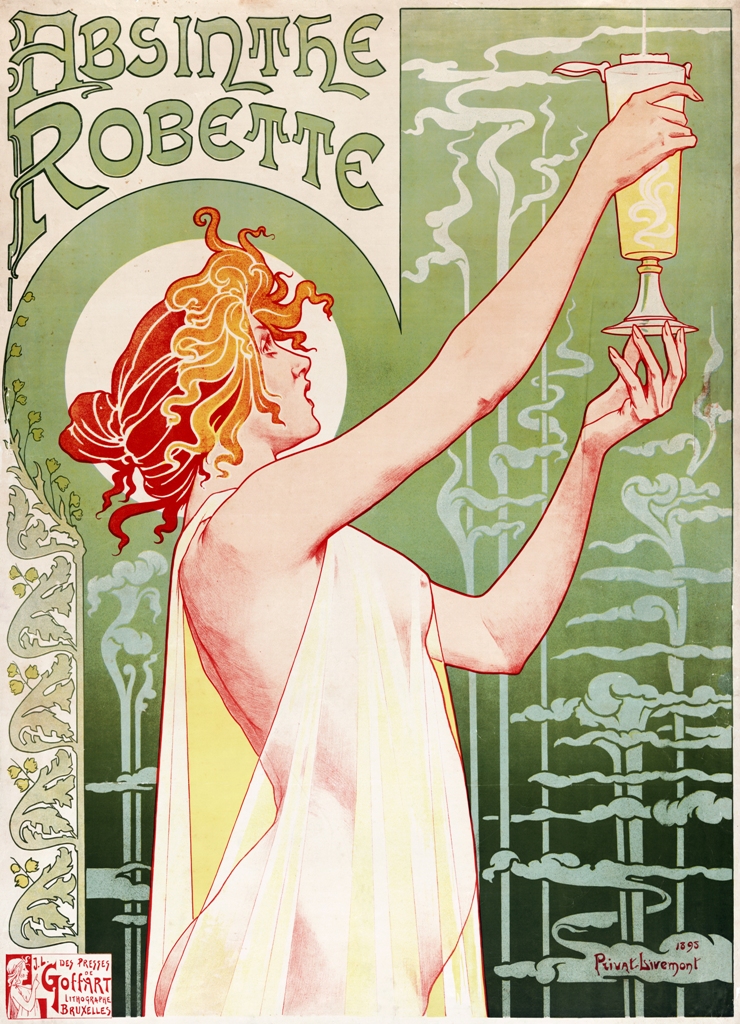

Advert for Absinthe Robette showing “la fee verte”.

The relationship between absinthe and New Orleans is one built from the roots of French boho expressionism. A spirit to inspire the muse in us all, famous poets, artists and musicians such as Charles Cros, Vincent Van Gogh, Oscar Wilde and Ernest Hemingway to name a few, were well documented fans. While respected artists and scholars all, they were also equally raving alcoholics to which absinthe supplied but one of their daily satiations.

Not dissimilar to the New Orleans of today, around the beginning of the 20th century it was a city of artistic creativity and inspiration. Visitors today can still experience a part of this history at the Old Absinthe House bar on 240 Bourbon Street where beautiful ornate spigots used for watering down absinthe can still be seen built into the bar top. At some point during Handy’s tenure at the Sazerac Coffee House, an absinthe rinse was apparently added to the final Sazerac cocktail serve. As an aromatic compliment to the anise notes off Peychauds bitters, this new touch added a final complexity unsurpassed in any other classic cocktail (in my humble opinion).

“After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.” – Oscar Wilde

There is arguably no other spirit in history more falsely persecuted than that of absinthe. Widely believed to hold hallucinogenic effects from its primary ingredient Grand Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), it is from this popular rumour that the common bohemian gentry whom frequently enjoyed the beverage, developed the moniker of La Fée Verte (“The Green Fairy”). A muse who would appear to the absinthe riddled drinker and inspire creativity. This reputation and the spirits association to an often less savory class of individual, led to a ripple effect that would see absinthe banned across the modern world – [see : Absinthe – Life and Death of a Green Fairy].

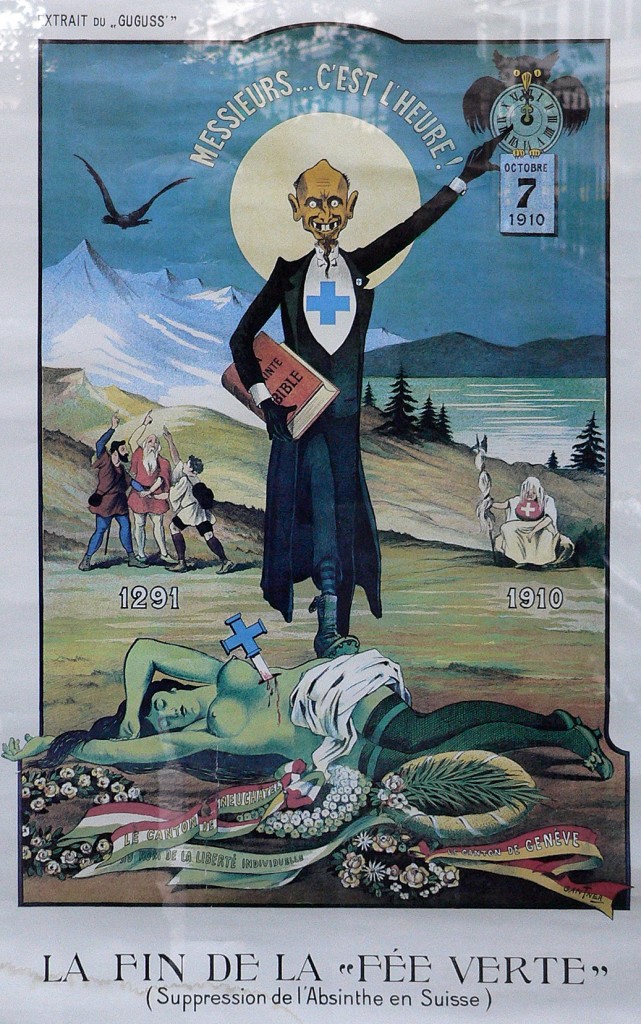

Absinthe is banned in Switzerland, as displayed by religious temperance stabbing the green fairy to the lament of the onlookers, 7th October 1910.

Entitled “The End of the Green Fairy in Switzerland” the image shows religious temperance pointing to the hour of prohibition having just murdered the green fairy with a knife in the shape of the Swiss Cross, 1910 – c/o Wiki Commons

Beginning with Switzerland in 1905, over the next two decades Belgium, Brazil, The Netherlands, Switzerland, France, Germany and Italy would ban the spirit with the USA joining the lynch in 1912. With the blame on absinthe squarely shouldered by its core ingredient wormwood, new spirits quickly emerged on the market to capitalize on the consumer love of anise yet without the said criminal ingredient. Today in France, pastis remains a popular early evening aperitif mixed, as was absinthe, with a good measure of water to dilute and louche (a cloudy emulsification) the spirit. To replace the now illegal absinthe from the Sazerac recipe, a number of different pastis liquors were used in its place yet by 1920 it mattered little as nationwide prohibition came to America and all serves were off. The Sazerac Company survived the dry 13 years as grocers and delicatessens until finally able to produced spirits again in 1934.

That same year, a new spirit named Legendre Herbsaint was sold to the New Orleans public for the first time. Created by J. Marion Legendre and Reginald Parker who are said to have made absinthe in France prior to it’s abolition, their recipe offered both a sans wormwood and local solution to the absinthe ban. Even in the mid 1930’s absinthe still carried an evil association as discovered by Legendre and Parker when their first product, released as Legendre Absinthe, was forced to rebrand replacing the incriminating word with Herbsaint (“sacred herb”). As a locally produced and highly aromatic anise liquor (initially bottled between 120 & 100 proof), the spirit became a popular addition to the Sazerac cocktail in replacement for the often softer pastis. By 1949, the Sazerac Company secured their claim on the cocktail once again by purchasing Herbsaint and solidifying the spirits role in the new Sazerac recipe.

Today, the absinthe conundrum remains and only recently has the guidelines surrounding the old American ban on absinthe (more accurately its chemical ingredient thujone) been revised. In this new definition, absinthe only needs to conform to a minimum of ten parts per million / per litre of thujone content which by chance qualifies the vast majority of absinthe’s available on the global market. As such, absinthe is making a resurgence in place of Herbsaint especially in the UK where bartenders and consumers alike are even taking it back to its brandy roots.

The Modern Sazerac

Ladies Night at the Sazerac Bar in the Roosevelt Hotel, New Orleans c.1950.

When visiting New Orleans today on the hunt of a classic cocktail, you’ll eventually be directed towards the aptly named Sazerac Bar at the Roosevelt New Orleans Hotel on Baronne Street. With the name holding no surprise as to the house specialty, the Sazerac Bar first opened its doors in 1949 where new bar owner Seymour Weiss also invited women inside for the first time outside of Mardi Gras.

Described as a “canny showman” by a member of the bar staff, Weiss recruited the aid of beautiful make-up girls from the popular Godchaux’s Department Store to add to the effect of glamour and glitz on the opening day. An event still known as the Storming of the Sazerac. Formally The Fairmont Hotel, The Roosevelt was reopened in 2009 after a four-year closure and USD$145 million refit in lieu of damages inflicted by Hurricane Katrina. In keeping with tradition, the newly restored art-deco Sazerac Bar was reopened with a reenactment of the Storming of the Sazerac, complete with ladies dressed to the nines in classic 1940’s attire.

Despite its namesake, the Sazerac Bar also became known as the home of another popular (and high maintenance) NOLA cocktail, the Ramos Gin Fizz. Charismatic Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long, famously flew one of the hotel’s bartenders to New York just so he could teach the cities own bar staff how to mix the drink correctly.

Salvatore “Maestro” Calabrese mixing up a classic.

On December 11th 2011, a new chapter was added to the story of the Sazerac when drinks maestro Salvatore Calabrese (bar owner, author, historian and master mixologist) hosted an evening of The Most Historic Cocktails in the World at the self entitled Salvatore’s Bar at the Playboy Club in London. The occasion allowed cocktail aficionados and select club members the chance to taste liquid history in a recreation of some of the most iconic cocktail recipes using the original ingredients and techniques of their time. Alongside 19th century classics like the Gin Cocktail, Brandy Crusta, Sidecar and White Lady were also ingredients including a rum from 1916, Cointreau from the 1930s and a Curaçao from 1860. Most coveted however and with a winning price tag of £2,500 (USD$4,200), came the penultimate Sazerac cocktail. Made from a freshly opened bottle of vintage 1805 Sazerac-de-Forge et Fils brandy, a dash of water and a sugar cube soaked in Peychaud’s and Angostura Bitters from 1915. Salvatore even completed the serve by using a shaker and barspoon from the same era and a 150-year-old rocks glass – [See the full length video of Salvatore making each drink].

And so to answer the question, what is the authentic Sazerac recipe? I leave the choice of spirit, rinse, ratio and stirs, entirely to your own election but implore you on two counts; keep Peychaud’s in the mix, he’s earned it and never be in a hurry to make one – even when you’re in a hurry to make one. Therein lies the skill.

References

- New Orleans Declares Sazerac Its Cocktail of Choice– National Public Radio, June 26, 2008

- Peachridge Glass:Peychaud’s Cocktail Bitters – L.E. Jung and his Gators

- Sazerac Company Inc

- New Orleans Pharmacy Museum, NewOrleans, United States

- McCord Museum, Montreal, Canada

- The Nation Magazine. In Congo Square: Colonial New Orleans by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, 10 December 2008. – Online Publication

- Jade Liqueurs:Best Absinthe – Website by T.A. Breaux

- Salvatore Calabrese

- NOLO.com: Roosevelt Hotel Celebrates the 1949 ‘Storming of the Sazerac’, by Todd A. Price, September 19, 2011 – Online Publication

- Old New Orleans: A History of the Vieux Carre, Its Ancient and Historical Buildingsby Stanley Clisby First edition 1936 – Google Books

- Bitters: A Spirited History of a Classic Cure-All with Cocktails, Recipes and Formulasby Brad Thomas Parsons, 2011

- The Roosevelt New Orleans

- Fix the Pumpsby Darcy S O’Neil, 2010

- Ancestry.com:Online immigration, birth, marriage, death and census records. New Orleans 1800-1890

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.