You’ll often hear distillers say that as much as 50% of a bourbons flavor and 100% of its color comes from the charred new Oak barrel that the bourbon is aging in. Though some might argue on the percentages, they all agree that the barrel is a key ingredient in the final color, nose and flavor of bourbon.

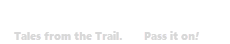

If you look at old distillery maps like the one below from the 1800s it’s not unusual to see a Cooperage, Coopers Building or a Cooper Shop on the same property as the distillery. In today’s distilled spirits world as more and more businesses specialize in doing one thing, it’s not common for a distillery to own its own cooperage. In looking at the large distillers today, there’s only one large distiller and that’s Brown-Forman. The company purchased an old woodworking factory in 1945 and one year later had a fully operational cooperage. The first barrel ever filled from the cooperage was filled with bourbon from the company’s first product, Old Forester Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.

A New Cooperage Tour and Visitor Center

We recently had the opportunity to tour the Brown-Forman Cooperage in Louisville, Kentucky to see exactly how barrels are made. In fact, with the recent launch of the company’s Cooper’s Craft Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey, this location now has a brand new visitor center or what’s often referred to as a Homeplace. Brown-Forman actually has two cooperages. In July 2014 the company celebrated the grand opening of a second cooperage in Decatur, Alabama. Between the two cooperages, they provide all the barrels for Jack Daniel’s, Early Times, Old Forester, Woodford Reserve and Coopers’ Craft.

Watch the video and you’ll see the journey from stave to fire tunnel to a finished barrel rolling off the assembly line.

Once inside the visitor center, the tour begins with a display called “Life of a Barrel.” It’s a collection of 53 gallon barrels cut in half to show the production process from raw, toasted, charred, chiseled to aged wood barrels. We’ll take you through each of these steps as we walk through the cooperage. One exception in this group is the Chiseled barrel. That one is used exclusively for a custom version of Cooper’s Craft Bourbon and Jack Daniel’s Frank Sinatra Whiskey. Those extra grooves cut inside the barrel provide about 40% more wood surface.

From here we picked up our safety gear that included a fashionable reflective vest (I think it was more to protect the employees so they know there were people walking around that have never been here before), earplugs and safety glasses. The earplugs and glasses are no joke, this is an active cooperage with lots of wood being moved around, heavy barrels, screaming loud tools and hammers, sharp saws, metal stampers and of course fire. Pro Tip: Stay behind the yellow lines.

Greg Roshkowski, VP Director Wood Planning-Procurement and Processing shows visitors “How to Raise a Barrel.”

When you walk in the door of the cooperage, there are two distinct smells that hit you right away. You’ll immediately get hit with the smell of fresh cut wood from all the sawing and planing and then smell of burning oak. The smell brings back warm memories of summertime and sitting around a campfire enjoying S’mores.

Our tour was lead by Greg Roshkowski, VP Director Wood Planning/Procurement and Processing for Brown-Forman Cooperage. Greg said the people that are assembling the barrels are, “Raising one barrel about every 45 seconds. They start with the bung stave of about 5.5″ wide. This is also the stave where the rivets will lineup. From there, they are going narrow-wide, narrow-wide and counting staves in their head.” Their goal is to end up with between 29 to 33 staves in a completed barrel. There is no exact number because wood is an organic product and they are trying to maximize every square inch they can get out of each stave. If you take a close look at some of the photos you’ll notice each stave is cut to a specific angle and shaped to produce the round barrel with an extremely tight fit. Remember, there’s no glue used in the process so these joints must be precise.

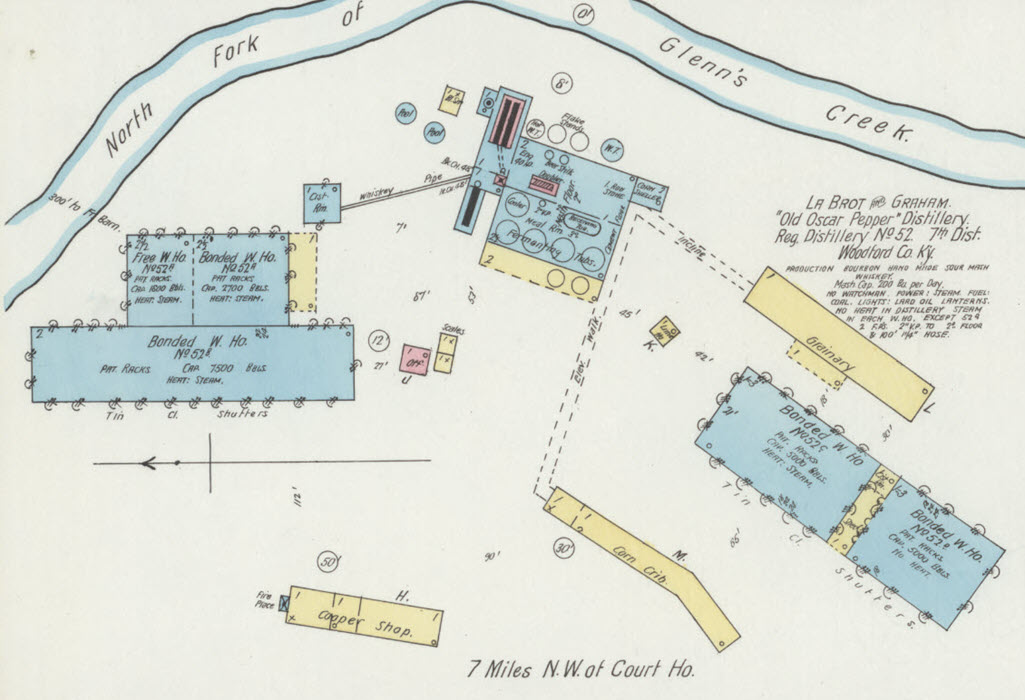

It Starts in the Forests of the ‘American White Oak Belt’

Raising a barrel starts with the wood. Technically, the TTB says bourbon whiskey must be aged in, “charred new oak containers.” There isn’t anything in there that says what type of oak is required but the standard is American White Oak – Quercus alba. You may see some distillers using French Oak or in the case of some Pacific Northwest distillers Oregon White Oak – Quercus garryana. As long as it’s oak, it meets the TTB definition for bourbon. We believe this broad definition is best for the industry and allows distillers to experiment with many different types of oak.

The white oak for Brown-Forman and most cooperages in the area come from a large portion of the Eastern U.S. ranging from Minnesota to New York down to Georgia and across to Texas. The age and the diameter of the oak tree will vary. They are looking for a tree that is optimally 16″ to 20″ in diameter and ideally no branches for the first 25 to 30 feet. Branches mean knots and knots mean leaks. They try to get two sets of 36″ staves and a pair of 24″ pieces for the heads from each tree.

Air Seasoned then Kiln Dried

Once the wood is delivered to the cooperage, it’s left outside to air dry. The amount of time allowed for air drying will vary by cooperage and could vary by bourbon. In the case of Brown-Forman Cooperage, they let their oak air dry outdoors for six to nine months. After that, the wood is taken inside and placed in a kiln where they bring the moisture level down to about 12%. After that, it’s ready for milling.

Creating the Round Barrel Heads

The head pieces start out with 24″ pieces of oak. Unlike the barrels that will end up as a cylinder, these parts are a little different because need to stay flat to avoid leaks. The pieces are aligned and doweled for a tight fit. There is no glue or adhesive used during any step of the barrel making process. As they continue to invest in this location the dowel process will eventually be replaced by a tongue and groove process to speed up the head building operation.

Once the square pieces are forced together, it’s off to another cutting station to be made round to match the opening of the barrel. From there, it’s time to char one side of the head to maximize the flavor from the oak barrel. The leftover corner pieces are used to fuel the onsite boiler or bagged then shipped off for horse bedding.

Raising a Barrel

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Once the barrels are raised and held together with their temporary hoops, it’s time for steaming the wood to help make it more pliable so it can be bent into shape without splitting or cracking. After it goes through the steam tunnel, it’s time for toasting. Toasting is kind of a flash fire to seal the juices into the wood. This occurs before the barrel is charred. Watch the video to see how these professionals build one barrel every 45 seconds.

The Char Tunnel – Charring the Barrel

Let’s face it, this is the coolest part of the journey. This is when the barrel gets lit on fire. What’s better than this? It’s got fire, smoke and steam. And don’t forget that smell. Barrel charring generally ranges from a No. 1 (light) to a No. 5 (dark.) 5 being the longest therefore darkest or heaviest char. Just like modifying the grains in a mash bill or yeast during fermentation, changing the toasting and/or char level in a barrel will have a dramatic influence on what will happen to the bourbon inside the barrel. In today’s world, some products like Woodford Reserve Double Oak get placed into a second barrel to get another round of fresh oak to create its own unique flavor.

Different cooperage use different methods to char their barrels. Some use leftover oak wood chips to char the inside of their barrels while others use gas to get a more consistent char from barrel to barrel. In the case of Brown-Forman, as you can see in the video, they use gas that provides a short burst of flame to get to their char level.

After the charring is complete it’s time to cut the crozier, the rabbit like cut that will hold the top and bottom barrel heads in place. Once the croze is cut and the heads are in place it’s time for the permanent metal hoops.

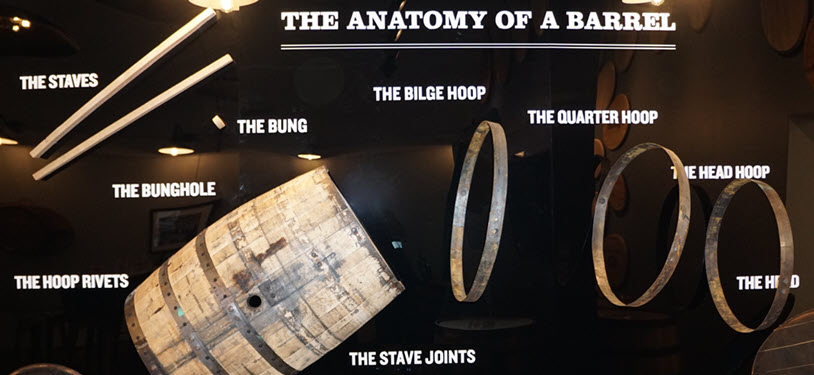

Installing the Head, Quarter and Bilge Hoops

53 gallon barrels get a total of six metal hoops. The hoops include the head irons, the ones nearest the heads, the quarter hoops and the bilge hoops, the largest hoops that will rest nearest the center of the barrel. This task is quickly accomplished at Brown-Forman with a hydraulic press system. The head hoop is pounded in place first followed by the bilge hoop then the quarter hoops. The process is duplicated for the other end of the barrel and the hoops are complete. Again, there is no glue or adhesive used to hold the barrels together that might affect the flavor of the bourbon whiskey. It’s a tried and true method that’s been used for thousands for years. Oh and you can pretty much feel the floor shake during this process.

What’s with the BB on the Rivets?

At Brown-Forman Cooperage, all the hoops are made in-house from large spools of banded steel. A close look at the rivets reveals the initials BB. Whenever you see a barrel with these initials in the U.S. or in Scotland aging Scotch, you’ll know this barrel was made by Brown-Forman.

The Final Steps – Drilling the Bung Hole and Pressure Testing

The next and final steps are to drill for the bung hole in that 5.5″ stave. Incidentally, the rivets are lined up with the bung hole. The hole is cut at a precise angle to hold the bung. Once the bung hole is cut the barrel is filled with approximately 1.5 gallons of water and it gets a temporary bung for pressure testing. The barrel is tested with up to 7 lbs. of pressure. If it passes the test, it gets a temporary plastic bung and it’s ready to head to the distillery. If it fails the test it’s time for some extra TLC.

The Coopers’ Station

Wood is an organic product and no two pieces are alike and occasionally barrels leak. Fortunately at this point they are only leaking water so it’s not a problem. The barrels are rolled to the Cooper’s Station for repair. Repairs vary from barrel to barrel and may include removing some of the hoops, the heads or even a stave or two if there’s a bad one. Small holes or imperfections are filled spiles, wedges or reeds. Once the repair is complete the hoops and heads are reinstalled only this time by old school methods with a hammer and a chisel. The barrel is tested again and assuming the leak is repaired it’s rolled down the line on to the truck and headed to the distillery.

The barrels are generally filled with white dog whiskey within three to five days. Depending on the time of year and outside temperatures barrels can start to dry out in five to seven days. If they start to detect barrels may dry out before filling they water them in the trailer. They spray them with water from a hose to prevent the hoops from slipping.

Greg Roshkowski says the Brown-Forman Cooperage raises between 2,500 and 3,000 barrels per day or about 600,000 a year. To put that in perspective, that’s enough barrels to fill 25 rickhouses with 24,000 barrels each. Once there, they rest for anywhere from four to six years, some longer depending on taste.

Looking for American Oak barrels for your distillery? Visit our comprehensive Supplier Directory for Barrels and Bungs and all your distillery needs.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.