Growing up in Kentucky bourbon country one can’t help but to be immersed in the art and science of tasting, distilling and enjoying bourbon. People that are deeply rooted in the amber spirit know it’s much more than a drink, it’s a lifestyle. And in the case of Peggy Noe Stevens and Susan Reigler co-authors of the new book ‘Which Fork Do I Use with My Bourbon? Setting the Table for Tastings, Food Pairings, Dinners, and Cocktail Parties‘ they understand that most importantly bourbon is meant to be enjoyed in good company.

The books authors are not authors that decided to write a book about bourbon. They are both bourbon aficionados that decided to write a book about their love for bourbon. Peggy Noe Stevens is president of Peggy Noe Stevens & Associates, founder of the Bourbon Women Association, and the first female master bourbon taster in the world. She’s also a recent inductee into the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame.Susan Reigler is a former restaurant critic for the Louisville Courier-Journal and a current correspondent for Bourbon+ and American Whiskey magazines. She’s authored or coauthored six books on bourbon and was recently inducted into the Order of the Writ. We would like to tell your more about the Order of the Writ but it’s kind of a secret fraternal organization that we hear embraces bourbon education, responsibility, environmental stewardship, history, scholarship and an unwavering commitment to the furtherance of bourbon. We’ve probably said too much about it.

Among its many chapters ‘Which Fork Do I Use with My Bourbon?’ offers a step-by-step guide to hosting a successful bourbon-tasting party—complete with recipes, photos, and tips for beginners and experienced aficionados alike.

The book includes expert tricks of the trade on how to set up a bar, arrange tables, and pair recipes with specific bourbons and much more. Once readers are ready, Stevens and Reigler move on to advanced pairings for the bourbon foodie and present two innovative examples of tasting parties—a bourbon cocktail soiree and, of course, the traditional Kentucky Derby party. Inspired by the hosting traditions of Kentucky distilleries, this book will introduce casual fans to bourbon-tasting methods and expand the expertise of longtime bourbon enthusiasts.

‘How to Do a Bourbon Tasting’ from Bourbon Specialists Peggy Noe Stevens and Susan Reigler

To give you a true taste of this new book we got permission to share an excerpt that is guaranteed to whet your appetite. Before we get started there is no right or wrong way to enjoy bourbon. One thing to keep in mind is that most bourbons have spent four plus years aging in an American Oak barrel patiently waiting for the master distiller to give the affirmative nod to say this bourbon is ready, ready to be bottled, ready to be shared and ready to be enjoyed. So of course you can enjoy your bourbon any way you like it neat, on the rocks or in a cocktail but we recommend you sip and savor this amber spirit to appreciate what it took to make it this far.

And now, without further ado let’s get started. This is not the entire chapter but it’s enough to get your eyes, nose and pallet engaged to make you want to pick up a copy and as Paul Harvey used to say get “The rest of the story.”

—– How to Do a Bourbon Tasting —–

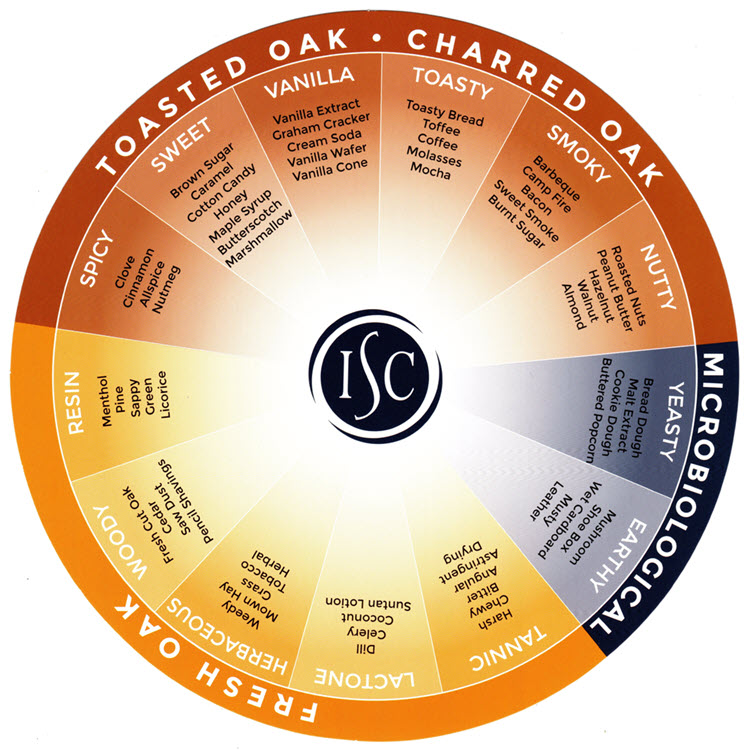

Vanilla or caramel. Cherries or peaches. Cinnamon or nutmeg. Almonds or pecans. These may sound like choices for a recipe, and in a way, they are. These flavors and many, many more are commonly detectable in bourbon. Distillers carefully craft their spirits with certain flavor profiles in mind. A bourbon tasting can offer a tantalizing mix of mystery and hints of the familiar. We all know how an apple tastes, but would we expect to encounter that flavor in a glass of whiskey?

With decades of experience introducing people to bourbon, we know how to heighten your senses. Everyone comes to the table with food memories, and the flavors encountered in bourbon are those from your fruit bin, bread box, spice cabinet, and secret cache of candy. Whether you and your guests are new to bourbon or seasoned enthusiasts, your party will be energized by a bourbon tasting. Participants will debate which fruit, nut, and spice flavors they can detect. One person’s apple may be another’s pear. Which is a better descriptor, corn or corn bread? Your guests will ask questions. They will vote on favorites. In short, they will have a great time, and your party will be talked about for weeks—or longer.

Bourbon-Tasting Basics

For a basic tasting, you should probably have no more than three bourbons. Even two can work well, especially if they have very different flavor profiles. The recipes for bourbon fall into three major categories: traditional (corn making up three-quarters to four-fifths of the mash bill, with rye and malted barley constituting the rest), wheated (wheat used in place of rye in the mash bill), and high rye (corn percentage only about two-thirds). Here are some examples:

[table “” not found /]Of course, all bourbons are distinctive, but most people will be able to notice marked differences when you choose bourbons from two or three of these categories.

Glassware

Tulip-shaped glasses are preferred, whether you use small wineglasses or Glencairn whiskey glasses. The bulb shape helps release the aromatics in the bourbon, and the relatively narrow throat or chimney traps and concentrates them near the lip of the glass.

If you are hosting more than a handful of guests, you may want to provide just one tasting glass to each participant. Each person should rinse her or his glass with water between tastes and drink the water, which serves the dual purpose of cleaning the glass and cleaning the palate. Plus, one glass per person means less glassware to be washed later!

Tasting Mats

Tasting mats are especially useful if you are prepouring the samples.

In addition to reserving a space for each sample, the mats can provide information about each bourbon, such as distillery, proof, and mash bill. Depending on the tasters’ level of experience, you can use either a basic mat or one with more detailed information.

Nibbles

Certain foods pull out different components of a whiskey’s flavor. Have little dishes of the following on hand for the tasting. Use them, in the order listed, for the first bourbon you taste. Doing this will help you understand the major flavor components.

Bourbon Facts Bourbon is not just a spirit. It’s a lifestyle. It’s impossible to appreciate bourbon without understanding a bit of its history. At the beginning of the tasting, take a few minutes to give your guests some of this background.

More than 90 percent of bourbon comes from Kentucky. The Bluegrass State’s master distillers have a treasure trove of the world’s finest ingredients. Calcium-rich limestone-filtered water is one of the hallmarks of fine bourbon (and the key to strong bones in Kentucky Thoroughbreds). The water is iron free, so the whiskey will not have a bitter flavor and will not turn black (a great color for coffee, but not for whiskey). The high mineral content also gives the yeast a nutritional boost as it carries out the important function of fermentation.

Bourbon must be at least 51 percent corn, which is largely responsible for establishing its flavor. (If bourbon is sweeter than other whiskeys, consider that corn bread is sweeter than other breads.) Rye or wheat and malted barley are also part of the mash bill the distiller uses to create the bourbon.

Yeast adds a delicious nuttiness, as well as fruit and floral aromas. Distilleries’ yeast strains are proprietary, and some date back to the 1800s. A yeast strain may determine whether the fruit note in a bourbon is apples, pears, peaches, or something else. Sweet spice notes, such as cinnamon, also come from certain yeast strains.

Age matters. That’s why master distillers are patient and very particular about the amount of time they age their whiskey in barrels, like steeping a tea bag in water. The longer the maturation process, the richer the color and the deeper the wood notes pulled from the barrel. White oak barrels act like large blocks of sugar, releasing vanillin (vanilla). Once the inside of the barrel is charred and toasted, the wood sugar is caramelized, like the topping of a crème brûlée. All the color and most of the flavor of bourbon come from its time in the barrel. Older is not necessarily better, though. Thanks to hot Kentucky summers, a lot of evaporation occurs during aging. Bourbons in their teens risk becoming tannic. That said, some very old bourbons are very good indeed. But you pay a premium for them because there is less whiskey in a fifteen- to twenty-year-old barrel than in a seven-year-old barrel. For every year of aging, about 5 percent of the whiskey is lost to evaporation.

The lowest-proof bourbon is 80 proof (40 percent alcohol). A higher proof may add complexity, but it may also “lock up” some of the flavors with the alcohol. Adding a few drops of water can “open up” a higher-proof bourbon to reveal multiple flavor layers, especially the fruity notes. A good rule of thumb for tasting is to start with the lowest-proof bourbon and proceed to the highest.

All these factors contribute to bourbon’s complexity—what we call following the flavor map of spice, sweet, savory, fruit, and earthy—and they are key to any great bourbon. Generally, the higher the quality, the more complex it is.

The Tasting Steps

When tasting, there are four things to consider: color, aroma, flavor, and finish. That’s easy enough, but you have to go beyond flavor and consider complexity to determine how to pair a particular bourbon with a specific food (examined in detail in the next chapter).

Step 1—Color. Every bourbon gets its depth of color from the barrel in which it was aged. In general, light-colored bourbon has matured for fewer years than dark-colored bourbon. However, if a barrel has a very dark char, even a relatively young bourbon may have a rich color. Each distillery chooses the amount of toasting (how long the wood staves are heated) and the char (blistering of the interior of the barrel with an intense flame).

The toasted layer (also called the red layer) is where the bourbon picks up all its color and much of its flavor during aging. Toasting can be light or dark, just as you can set the level on your kitchen toaster. The char blisters the wood so the whiskey can easily move in and out of the red layer. During hot summers, the wood expands, and the whiskey migrates into the red layer. The cold of winter causes the wood to contract, and the bourbon is squeezed back into the barrel.

Examine the glass against a white background (a tablecloth or napkin works well). Look for a rich amber color that has sparkle and bounce. View the bourbon for clarity and delicate highlights. Note the following colors:

[table “” not found /]Step 2—Aroma.Trust your nose! It is responsible for 75 percent of your flavor perception. You might feel compelled to dive into all the possible flavors of bourbon. But especially in the case of higher-proof bourbons, don’t overwhelm your sense of smell by putting your nose too far into the glass. Instead, rest the glass under or to the side of your nose and move the glass toward you and away from you as you distinguish the aromas. Bourbon aromas tend to have layers. At first nose, many people notice the vanilla and caramel; then you can try to go deeper.

After the first nosing, turn your head and “blow away” the scent through your mouth. Now nose again. You’ll find that the initial hit of alcohol in the first nosing is gone and you can smell the other aromatics. Be aware of the spices, fruits, nuts, and other aromatics; take your guests through each category and ask them what they detect. These aromas define the structure. Add a drop or two of water to release fruit notes and reveal hidden aromatics.

Step 3—Flavor and Mouthfeel. After building the anticipation of aroma, the best part, of course, is tasting! Let a small amount of bourbon rest on your tongue and then, as we say in Kentucky, “chew” on it. Some bourbons coat your tongue, while others seem thin. This is the mouthfeel. The flavors will astound you as you focus on the sensation of the whiskey in your mouth. Unlike wine tasters, who pull air into the mouth, you want to blow air out of your mouth to break down the alcohol and get to the core of the flavors. As described earlier, try the fruit, nut, chocolate, and caramel nibbles in sequence for the first bourbon in your tasting. This will help you tease out the flavor layers. If you like, you can do this with the other bourbons in your flight (tasting), but it’s not necessary. We recommend cleansing the palate with oyster crackers and water between whiskeys. Above all, relax and enjoy the flavors!

Step 4—Finish. Peggy’s father used to say, “A great bourbon will ‘wrap’ your tongue like a satin ribbon.” The taste is rich and warm. The finish, or aftertaste, may be dry and sweet or spicy and bold. The true test is whether the finish lingers as if the liquid were still in your mouth. The longer it lingers, the better quality the bourbon. If you return to the empty glass later and there is a lingering aroma, that’s the sign of a good bourbon.

There Are No Wrong Answers

No single bourbon has all the aromas and flavors in the accompanying list of descriptors. But better bourbons are usually more complex and encompass a greater number of them. The most important thing to remember is that you are tasting, not drinking. Take small sips, and pay attention. The larger your “flavor vocabulary,” the better your ability to describe what you are tasting. For example, there may be a note of butterscotch in the bourbon, but if you’ve never had butterscotch, you won’t have a word for the flavor you’re tasting. And remember (we cannot emphasize this enough), everyone’s palate is different. One person’s cinnamon may be another’s nutmeg.

For basic tastings and for people who are not familiar with bourbon, you may want to provide some sample descriptors from the list. Having multiple options to choose from is easier than pulling adjectives out of the air! If you and your guests want to take an even deeper dive into bourbon flavors, or if you are experienced whiskey lovers, you can use a more advanced tasting mat and rate the intensity of each type of flavor.

Examples of Flights

Once you have hosted a basic tasting, subsequent parties can be centered around bourbon themes. Try tasting bourbons that are the same proof, bourbons aged more than ten years, or bourbons of the same style (traditional, wheated, or high rye), or compare bourbons to Scotch, Irish, or Tennessee whiskeys.

Age

Taste the bourbons in order from youngest to oldest. You’ll have to find bourbons with age statements on their labels, which is a little harder than it used to be, since many distilleries have dropped age statements. However, if a bourbon is less than four years old, the age must be included on the label (you may see “Two Years” or “36 Months”). Here are some bourbons that still display age statements: Very Old Barton (6 years), Old Ezra (7 years), Knob Creek (9 years), Henry McKenna Bottled-in-Bond (10 years), I. W. Harper (12 and 15 years), and Elijah Craig (12 years). Also, many private selections that can be found at retailers have age statements. For example, bottles of Four Roses Private Barrel Selections give the age in years and months, such as “11 Years, 3 Months.”

Barrel Proof (Cask Strength)

These bourbons have not had their proofs adjusted with distilled water before bottling. They always benefit from the addition of a little water during tasting to tame the alcohol heat and unlock the flavor layers. Examples are Booker’s, Elijah Craig Single Barrel, Four Roses Single Barrel Private Select, Maker’s Mark Cask Strength, Old Forester 1920, Stagg Jr., and Wild Turkey Rare Breed.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

The full chapter goes on to discuss ways to introduce different types or styles of whiskey that you can pair together for tastings like American Whiskey vs. International Whiskey (though technically it’s not a bourbon unless it is made in the U.S. but it may have a similar mash bill). And you are also encouraged to taste bourbon from different parts of the country. It’s true that the vast majority of bourbon is made in Kentucky but we highly recommended you try bourbons from different states to experience the regional terroir. Kentucky is located in the center of the U.S. and experiences all four season to varying degrees. A bourbon with the same mash bill made in Northeastern states like Washington or Oregon or a deep southern state like Texas where the climate is hot and dry year round may taste very different. Geographic regions can play a big role in the final taste of a bourbon.

And as always we highly recommend that you drink responsibly at all bourbon tastings.

This is one of many tales from Which Fork Do I Use with My Bourbon? Setting the Table for Tastings, Food Pairings, Dinners, and Cocktail Parties. There is no right or wrong way to drink bourbon―in a cocktail, straight up, on the rocks, or with a splash of soda. You will never know which is your way until you try them all. This hardcover book features more than 200 pages with stories and beautiful photography to help you on your bourbon journey. You can pick up your own copy of Which Fork Do I Use with My Bourbon? here.Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.