-

Barrels of Woodford Reserve bourbon maturing in a Kentucky rickhouse. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Pus. Yep, pus. Ok, not the most obvious way to open an article on ‘maturation’ but according to the earliest use of the word (Etymology Online), it’s in 14th century medieval Latin where we find the birth term maturatio(n-) or maturare to describe a doctors act of “encouraging suppuration” or discharging pus from a boil or wound. Charming.

From there this early definition evolved through the years to define anything that is “ripe” or “ready of age” until hitting a Wikipedia page some 700 years later as “the emergence of personal and behavioral characteristics through growth processes”. Still a bit too close to its original definition for comfort isn’t it? Admittedly not the way we typically view our beloved oak-aged spirits. For our purposes however, we’ll focus on the modern use of the term and the magic that takes place between a new fill spirit and a cask made of oak.

As mentioned in Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Part 1: Know Your Casks, if there is one thing that we all go a bit crazy for, it’s oak matured booze. In expression of this fact, there is currently 109 registered whisky distilleries in Scotland, five in Ireland, one in Wales, at least three in England (many start-ups), six in Australia, eight in Canada, six in India, six in Japan, nine in Sweden, and even nations like New Zealand, Thailand and Korea are getting in on the action. The elephant in the room however is obviously the United States with almost 700 registered distilleries to date and more opening every week. Even more striking however is a statistic in Entrepreneur Magazine which states that merely a decade ago, there were only 70. And with the increasing number of whiskey distilleries also comes an equally increasing demand for oak.

Here’s the three part series in case you missed one.

Part 1: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Know Your Casks

Part 2: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Maturity is Not Age

Part 3: Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Location, Location, Location

Stay Informed: Sign up here for our Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

While each of the above distilleries will be using their own unique techniques to produce their own unique styles of matured spirit, for the sake of simplicity, we will be focusing primarily on the two most iconic; Single Malt Scotch and Bourbon Whiskey.

According to the Scotch Whisky Association, 60%-80% of a Single Malt whisky’s flavor is attributed directly to maturation. For American whiskey it is around the same ratio however it’s important to point out that the Scotch industry use casks which have already held American whiskey in them while Bourbon is restricted to only using new American oak casks for maturation. Like using one tea bag for two cups of tea, the first cup will get the greatest infusion of tea in the shortest period while the second receives a slower, longer infusion at a more delicate release. So while oak influences a similar percentage of flavor in both American and Scotch whiskies, the oak release is quite different. Add to that further flavor variables such as the origin of the oak, a casks previous use and number of uses, cask sizes, stave widths, stave conditioning, maturation environments, toasting levels… and it becomes clear that to truly understand what’s really behind a bottle of ‘fully matured whisky’, one must pay attention to the detail.

Angels Share

Whether known as le ángeles cuota, la part des anges or 天使のシェア, the ‘angel’s share’ is an inescapable side effect of the maturation of any spirit despite large quantities of money invested by companies every year into researching ways of preventing it. As such, Scottish Excise allow whisky producers to write off 2% of their production volume every year as a natural effect of angels share. If you’re ever visiting Scotch distilleries in the Orkney Islands (Highland Park or Scapa), their average loss through angel’s share is only 0.5%-1% annually due to a unique micro climate influenced by the North Atlantic Trade Winds. As such, be sure to ask them what happens to the remaining 1% they’re allowed to write off…

For the Cognac industry, angel’s share equates to a loss of around 22 million bottles per year (according to the BNIC) making those greedy angels the second biggest consumers of Cognac globally after America. Cognac also has an entire ecosystem built around the angel’s share with a black fungus growing in the rafters and ceilings of maturation warehouses feeding off the alcoholic vapor. Officially called Baudoinia compniacensis (formerly Torula compniacensis), the fungus is well enjoyed by local insects which feed off it, in turn feeding the spiders which in turn keep other wood-boring bugs off the barrels and effecting the Cognac.

For the Bourbon, Rye and Tennessee whiskeys, their angels share is closer to 4% annually. With Kentucky recording average summer highs of around 32°C (89°F) compared to 19°C (66°F) in Scotland, both the level of evaporation and rate of maturation are greatly accelerated. It’s commonly believed that if two exact casks of liquid were placed in Scotland and Kentucky at the same time, the cask in Scotland would have to remain there for around three years to equal just one year in Kentucky. A good example of not judging a whisky merely by the age on its label. As the new industry mantra states;

“Maturity, not age”.

Seasoning

A process rarely mentioned by brand ambassadors yet regarded by many coopers as holding a greater influence on the final flavor characteristic of a mature spirit than the species of oak itself.

Seasoning refers to the vital practice of weathering freshly cut ‘green’ oak staves by naturally drying them to the point of tightening. As this happens large amounts of unwanted sap, moisture and heavy tannic compounds leach out of the wood yet retain core flavor elements such as sugars and vanillins. Often referred to as ‘air-drying’, the process is more accurately ‘weathering’ as wind, rain, heat, UV, air and even bugs play an important role in well seasoned oak. As with all things, there are however shortcuts and as such kilns can be used to speed up the process although it is well believed that only natural seasoning delivers the best aromatic profile with the softest level of tannins. In the case of American mills, most freshly cut oak staves spend at least 18 months seasoning with more specialist coopers only accepting staves which have seen 36 months minimum. In Europe, oak is grown in a more temperate climate than the Americas and as such requires longer seasoning periods. But like maturation, old isn’t always best. Too much seasoning and oak looses too much ‘life’ from the wood becoming brittle and increasing the chance of the stave breaking during lamination (bending).

Following the process of a classic Cognac mill, once an oak tree has been selected and cut down, the main trunk section is transported whole to a mill for splitting. An average of 4 barrels can be made from one good tree. The trunks are then quartered to obtain lengths for the barrel staves by a means of splitting and not cutting to prevent destroying wood veins important in later maturation. Splitting is done while the wood is still green as it is less susceptible to snapping. The staves are then planed into rough shapes (called merrain) and stacked outside for between three-five years after which they develop a silvery-grey finish darkened as a reaction to the seepage of heavy tannins. Only after this period, and once each stave has been inspected, are they replaned to the specifications of the cooper and shipped out for cask assembly.

Staves can even be stacked for seasoning in different ways depending on how the millers want the air to move between the wood piles relative to the species and age of oak (wider grain oak generally have more tannin and as such require longer seasoning). End piling, edge piling, crib piling, package piling, lap piling or combinations of them all, are stack variations specific to how the miller wishes to control the amount of airflow, impact of rain water, UV exposure or damp.

Back in the realm of whisky, the vast majority of color and flavor imparted on the distillate is made in its first twelve months of maturation. After which the characteristics of badly or well seasoned staves becomes more and more influential on flavor and the charring or toasting influences drop off.

-

Seasoning oak staves at a Courvoisier cognac mill. Note the darker, well-seasoned staves in the background against the younger ‘green’ staves in the foreground.

Of all the wood which arrives into a barrel mill, only about 20% will be used for making casks as the vast majority is discarded due to damage, knots or an abundance of sap. A common rule of thumb for millers is to season wood in or near its natural environment as cold frosty or hot and humid environments can negatively affect the seasoning process.

According to experienced American barrel broker Mel Knox, not even the stave width or thickness is as important to a spirits final flavor profile than well seasoned oak.

Many coopers in the wine industry prefer to season their own staves so they have a more direct control over this important process. For the spirits industry, producers are more concerned with buying casks from coopers with a reputation for producing tight barrels rather than well seasoned oak.

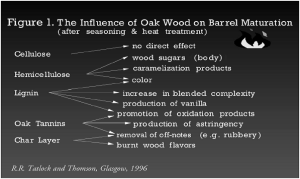

The Science

-

Taken from document – ‘The Composition of Oak and an Overview of its Influence on Maturation’. Courtesy of Distillers.org.

Of all of the species of hard wood in the world, there is a very good reason why we only use oak. As a member of the beech family, of the genus Quercus, oak has large radial grains of high density which grow straighter than the majority of other hardwoods making it perfect for tight cooperage. More importantly however are the natural chemical compounds found inside oak which impart flavors, sugars, aromas and body onto any liquid it interacts with. Flavors which are extracted by a cask during maturation are known as ‘cask-extractive congeners’.

For the effects of spirit maturation, there are five primary chemical constituents;

1. Cellulose

As the name suggests this compound is primarily composed of a form of glucose (sugar). Despite this is it does not impact on any notable flavor elements in a mature spirit but instead acts as a binding agent or polymer to help hold the wood together (i.e. essential in oaks ability to hold a tight cooperage). It is so effective at its job that it is the most abundant polymer in the natural world.

2. Hemicellulose

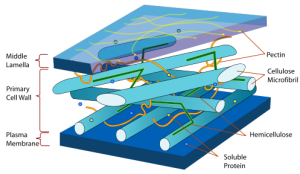

-

Section of the cell wall in a plant cell showing location of cellulose and hemicellulose. Courtesy of Wiki Media Commons.

While also a sugar based polymer, hemicellulose is not solely composed of glucose like cellulose but multiple sugars such asglucose, xylose, mannose, rhamnose, arabinose and galactose. Most importantly, these sugars are much more unstable than glucose allowing them to breakdown into their individual parts when stimulated by dramatic changes in their environment such as heat. It is these newly activated hemicellulose sugar condensation byproducts (furfural, hydroxymethyl furfural, maltol, cyclotene) which ultimately give us the deep brown colors and subtle almond, walnut, butter and maple notes from a lightly toasted cask. When the heat is turned up even higher to the levels of charring, most of these flavors are pushed aside by rich caramel and toffee. For hemicellulose to begin converting into color and flavor it needs to be activated by a heat of at least 140°C (284°F).

3. Lignin

-

The Pentlands Wheel, used to interpret the primary taste profiles of a specific whisky. Designed for the whisky industry by sensory experts at the Scotch Whisky Research Institute.

Anywhere there is a hardwood, there is lignin. While also a polymer, lignin is composed of two core structural parts, guaiacyl and syringyl. It is the direct result of these combined parts which is responsible for giving us sweet and spicy aromas, especially vanilla which is pulled from its chemical namesake – vanillin. Lignin congeners can be released very easily with only the smallest amount of activated heat however it’s the effect of heavy toasting and deep charring which breakdown the lignin further into steam volitile phenols responsible for delivering smoky flavor elements.

4. Tannin

As the name suggests, it is from tannin that we first derived tanning agents for leather and early dye’s giving us the common word – ‘tan’. While there are many different sources of tannin in the natural world (such as grape skins), oak tannin’s are unique in that most of them can be broken down not by adding heat, but by simply adding water. For this reason oak tannin are classified as hydrolysable.

Tannin which would otherwise overwhelm the majority of the other flavors in the wood. Acting primarily as a means of food storage for the tree, tannin helps protect the tree from fire and bacteria evolving into a natural bitter deterrent to insects in a similar way the coffee plant (Coffea) produces caffeine as a bitter pesticide. As a hydrolysable compound, seasoning (as above) is used to remove large amounts of bitter tannin from the oak prior to cooperage. That said, we still need a small element of tannin to supply us with oxidization and fragrances like cooked apple. More importantly however is the role tannin plays on long maturation. The wood chemical reacts slowly with the oxygen molecules in the spirit over time creating a new compound called diethyl acetal. This new compound ensures that a 20+ year old Scotch or Cognac for example, is left with rich and complex top-notes and not flat and insipid.

5. Lactone

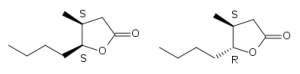

-

The face of Quercas lactone (3-Methyl-4-octanolide, cis and trans isomers). Also known as “stick man buys a rocket ship”. Courtesy of Wiki Media Commons.

Unlike the above components, lactones are only really relevant to American whiskey. Neither a polymer or sugar compound, lactone is a flavor element influenced by certain oils, soluble fats and waxes simply known as lipids which deliver a unique coconut-woody taste to a spirit. While present in all types of oak, lactones are found in their greatest quantity in American White Oak (with the exception of the rarely used Asian variety Quercas mongolica), releasing almost all of its flavor attributes in the first year of a first-fill barrels maturation. For this reason, Bourbon, Tennessee and Rye whiskeys all have outstanding vegetal characters when compared to Scotch which depends more on sweet, smooth polymers for flavor. Well seasoned and lightly toasted casks can release further amounts of lactone while deep alligator charring can react the other way, reducing its effect.

And charring after all, is a subject unto itself.

Charring Levels

Once a cooper has selected their oak type, cask size and seasoning qualities they can then select which level of thermal degrading to apply to the inside of the cask relative to the liquid it will have in it and the desired character of that liquid. The two most common types of thermal degrading are toasting and charring.

While toasting is a generally common practice for all casks used in wine, fortified wine and Cognac; charring is a direct result of our old friend American whiskey. ‘Straight Bourbon’, ‘Tennessee’ and ‘Straight Rye’ whiskeys are restricted by law to only using new charred barrels. And with over 700 registered whiskey distilleries across the United States of which Jack Daniel’s holds around 90 million US gallons of maturing whiskey at any one time, it’s no surprise that the majority of the worlds matured spirits are done so in ex American charred casks.

While Scotch cooperage’s also actively engage in charring, it’s predominantly for the use of reinvigorating ex American whiskey barrels. Traditionally, a barrel filled 4 times represented the end of a casks life but with such high demand and low supply of casks these days, most cooperage’s engage what is known as ‘dechar / rechar’ to further extend the life of a barrel. Dechar simply scrapes off the old alligator charring on the wood, taking the oak back down to a near fresh grain before the casks are then recharred at up to 1400°C ready for a fresh fill.

Generally speaking, the only time a whisky might meet a non charred cask is when they are adding a unique ‘finish’ to their spirit. Casks used for maturing Sherry, Port and Madeira are the best examples as they are almost always toasted since deep charring tends to overwhelm the delicacies of most fortified wines. Even when these same casks are purchased by Scotch producers for use as a finish to their whisky, they don’t need to be reinvigorated like ex bourbon barrels as doing so would remove most of the wine flavors already absorbed into the oak. And with the average sherry butt selling for almost 14 times the price of an ex American whiskey barrel, one wants to get ones moneys worth.

According to ‘Analytical Chemistry of Compounds Affecting Flavor in Single Malt Whiskies’ by Colin Brown, there are three reasons why casks are charred;

- To generate a layer of active carbon which removes undesirable flavor substances

- To effect the release and dissolution of flavor compounds such as vanillin during maturation

- To yield color and phenolic substances which result in new flavor compounds by oxidative interactive reactions

In basic terms, charring helps to open up micro channels allowing the spiri

t to absorb deep into the oak, further extracting aromatic aldehyde’s, increasing the release of vanillins and further absorbing undesirable flavor congeners in the process. By converting the top layer of oak into carbon charcoal, some of the wood sugars (hemicellulose) are converted into caramel notes while also acting like an activated carbon filter in a water bottle and filtering out unpleasant sulfur flavor compounds.

While charring is an exciting process to witness in any cooperage, as always, there is further devil in the detail.

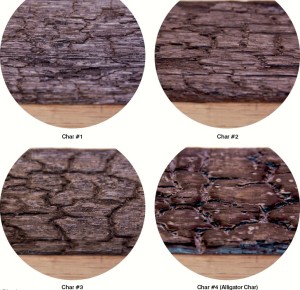

For a traditional whisky distiller, there are four core char levels simply graded from numbers 1-4 with the lower number representing a shorter exposure to heat and softer char level.

- No.1 Char: 15 seconds

- No.2 Char: 30 seconds

- No.3 Char: 45 seconds

- No.4 Char: 55 seconds (a.k.a. ‘alligator char’ due to its textured skin)

While the vast majority of American whiskey distillers prefer either a No.3 or No.4 char on their casks, a number of distilleries have experimented with even heavier levels such as Buffalo Trace releasing a No.7 Heavy Char Barrel Bourbon. The overall difference between a No.3 and No.4 char on a whisky is explained by the President and fourth-generation cooper of the Independent Stave Company – Brad Boswell,

“The lighter char preserves more of the natural oak aroma and flavor (think a little spicy, a little earthy, with a touch of cedar). The heavier char provides more color and caramelization. Tannins will vary between these two types of barrels. The heavier char can also provide for more of a sweet smoke note that is often desired.”

-

Flavor compounds released at variable toasting temperatures. Charring holds a similar profiles but at higher temperatures and richer caramel releases. Courtesy of World Cooperage.

In addition to the selected char level, the alcoholic strength of the spirit within also influences the rate and reaction of the char. The strength of an alcohol varies the release of flavor compounds in toasted or charred oak as it would if you were macerating your own aromatic bitters. A higher proof spirit tends to release richer levels of vanillins from char while lower strength sees less vanilla release but more sweetness from natural sugars.

Barrel sizes, conditioning, charring and chemistry all play essential roles in defining the final character of a mature spirit. If there was one major variable left in our investigation into Understanding Maturation, it’d be a beginning rather than an end.

In our final part, we’ll be examining the origins of oak, mapping the primary forests across Europe and the U.S., defining the differences between each, the variables in maturation environment and shortcut techniques like chipping and staving. Taking a day one lesson from real estate agents, we’ll be examining location, location, location.

Cover photo courtesy of WFPL.

Also see:

Understanding Oak Barrel Maturation – Part 1: Know Your Casks

Story Sources:

- Diffords Guide: Inner Geek, Cask Charring and Toasting – Industry Publication

- Whisky Science: Oaky Flavours – Blog

- Oregon State Library: Seasoning of White Oak for Tight Cooperage by E. F. Ramsmussen and J. M. McMillen – 1956

- International Journal of Food Science and Technology: The Effect of Cask Charring on Scotch Whisky Maturation

- WSET: Art of the Cooperage by Teddy Joseph – Paper

- Planet Whiskies: Whisky Distilleires of the World – Blog

- Sku’s Recent Eats: The Complete List of American Whiskey Distilleries & Brands – Blog

- Scotch Whisky Association – Official Website

- The Bourbon Review: Using Oak Barrels to Age Whiskey – Industry Publication

- Bowmore Wood Part 12/20: Dechr Rechar – Video

- Highland Park Single Malt Whisky – Senior Brand Ambassador, Martin Markvardsen

- Jack Daniels Tennessee Whiskey – UK Brand Ambassador, Cam Dawson