American distilling history is full of stories of settlers and second born generations heading west from home, finding new fertile lands, and setting up shop to practice their family’s heritage distillation techniques. In fact, if any one facet of American history is almost entirely disregarded in dusty old history volumes, it is distillation. This art and the economy produced by such spirits was intrinsically important to the foundation of our nation.

This is a ‘Day on the Trail‘ story from Alan Bishop, a southern Indiana Farmer-Distiller with a wide variety of interests including independent seed breeding, historical re-enactments, a researcher of distillery history and the Master Distiller at Spirits of French Lick in West Baden Springs, Indiana. Alan recently had the honor of traveling to two magical East Coast distilling locations including George Washington’s Distillery & Gristmill and Stoll & Wolfe Distillery.

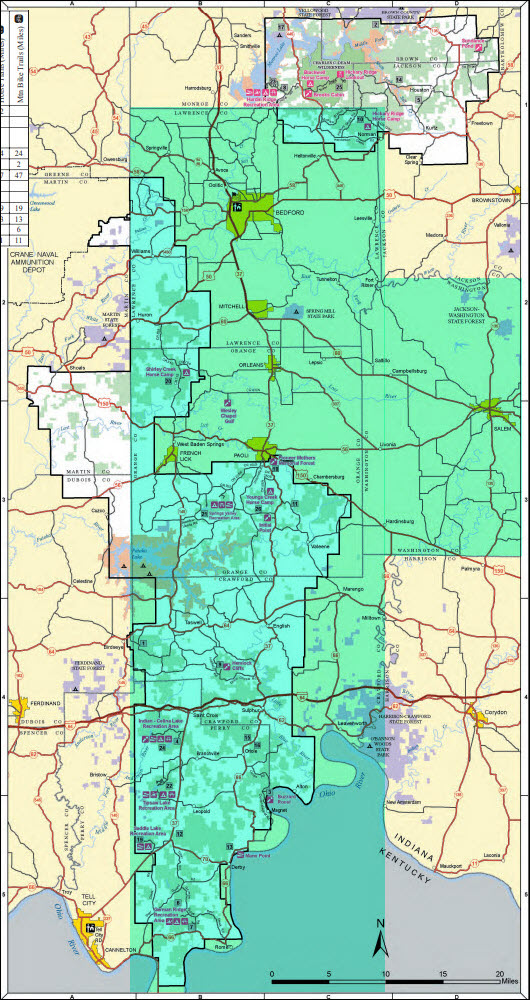

Such is the case with the Black Forest of Indiana, a story that I have been telling, revealing, and studying for many years now. Despite my family being from Kentucky, I was born a Southern Hoosier, and it is in the soil of the six-county region near the Hoosier National Forest that my roots are firmly planted. This is where I found my true calling to Alchemy in all its forms, and it is from the art of spirituous distillation that I derive my ‘living’.

Go West to Find Your Destiny

A great many of the early distilling families of this region found their way here from central and Eastern Pennsylvania. Upon arrival they discovered a land handsomely similar too and equally as beautiful as their home. It was land suitable for growing fruit orchards and various grains. In short order, however they found their preferred grain, rye, was all too often lost to storms in June as the grain ripened. This was mostly due to the tall nature and lack of stalk strength of those early heirloom rye varieties.

Distillers quickly adapted and turned their attention to apples, peaches, oats, corn, and wheat and began applying both the methods of their eastern home and ancestral Germany to their production. Over time, they slowly integrated new methods gained from those coming in from North and South Carolina as well as Virginia, from the Welsh, the Scotts-Irish, and later waves of German immigrants who brought a culture of fruit brandy.

Did Distillation Techniques Travel from the Mid-West Back East?

The question then is, did any of these distillers ever take anything much back East? Of course, there is Charles Everett Beam (grandnephew of Jim Beam) who worked in Pennsylvania and taught the late Dick Stoll (Born Nov. 28, 1933; Died Aug. 13, 2020) at Bomberger’s Distillery whose origins can be traced back to 1753 and was renamed to Michter’s Distillery in 1975. But otherwise there are not a lot of stories of this nature out there in the public domain from what I have seen. As someone who finds a real passion and love not only in distillation methodology but in developing it and sharing it with others, I have maintained a bit of a pipe dream of doing just this. Not on a full-time permanent employment standard of course, but as a passion project.

A Spiritual Journey – Distilling at George Washington’s Distillery & Gristmill

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

In November 2023, after a five year hiatus, I returned to George Washington’s Distillery & Gristmill at Mount Vernon in Alexandria, Virginia. The experience, as it was the first time, was highly spiritual for me, in terms of both the location and history. This was the original site of George Washington’s 2,250 square foot stone walled distillery built in 1797. Unfortunately, Washington passed away in 1799 and within a few years the distillery fell into disrepair and eventually ceased operation and later burned down in 1814. Almost two centuries later beginning in 2005 a project began to rebuild the distillery on its original site and two years later in 2007 the project was completed. Today, the distillery and gristmill operate like it did back in Washington’s day with the vast majority of operations done the way George did it in the 1700s, by hand with a series of wood fired pot stills.

Related Story

– A Day on the Trail at George Washington’s Distillery & Gristmill; A True American Treasure

– George Washington’s Distillery Celebrates 10th & 220th Year Anniversaries [Photos]

Today, the distillery and gristmill operation are led by Steve Bashore, a miller by trade, who acts as both the head distiller and miller. Bashore is an amazing fellow with a real knack for putting together people in a unique situation who to meet one another, often for the first time, and exchange ideas, and that is exactly what I did on this most recent trip just as I had done five years earlier.

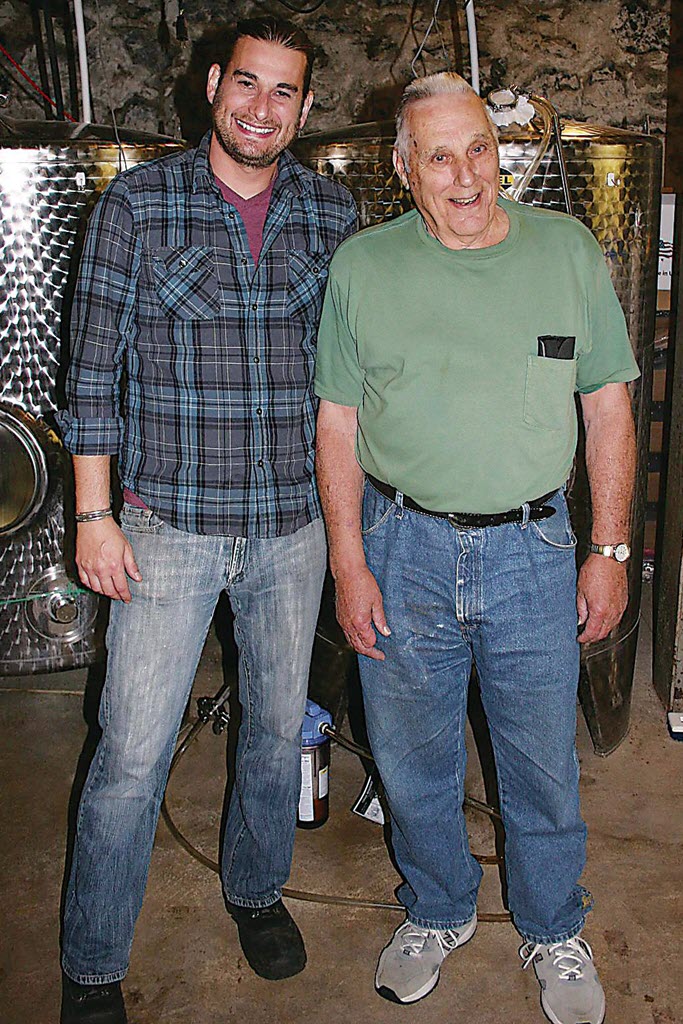

Among the variety of cider makers, distillers, reenactors, historic bakers, modern day spirits brand owners, collectors, and millers it’s not uncommon to strike up true friendship during the hands-on often back breaking distillation process. It was at George Washington’s Distillery that I first met Erik Wolfe of Stoll & Wolfe Distillery in Lititz, Pennsylvania. Erik and his wife, Avianna started Stoll & Wolfe in 2017 on the site that was once home to Michter’s Distillery which closed its doors in 1989 during the brown spirits downturn. Prior to this meeting, Erik and I had communicated through electronic communication for several years and exchanged information and spirits from time to time. After meeting in person and working together at George Washington’s Distillery we found ourselves in true comradery.

Erik and Aviana opened Stoll & Wolfe Distillery with the legendary Richard H. “Dick” Stoll who was the master distiller a Bomberger’s and later Michter’s. Erik was fortunate to live and work under Stoll’s tutelage for many years until Stoll’s passing in August 2020. Sometimes family isn’t blood, sometimes it is far more meaningful than blood, and that I believe is true of the gift Dick Stoll bestowed on Erik and the platform Erik and Aviana gave to Dick. It truly is an amazing “full circle” story, one which if you are unfamiliar with you should do some research into.

It was during my most recent trip to Mount Vernon that Erik and I began talks in earnest about working together potentially bringing other likeminded individuals into his distillery in Pennsylvania. The idea was to give others a chance to work in a unique environment where they could really flex their distilling skills and create highly differentiated products in a way that would benefit both the guest and the distillery. Erik, a very gracious and intelligent fellow, with a knack for sparking deeply meaningful conversation planted the seed for what was to come in my mind that day.

In the intervening months the prospect of the project began to take shape and by early January 2024 we had dates on the calendar for me to travel east to Pennsylvania. Now, bear in mind, both Erik and I are dreamers, the idea was enough for us to go on, planning not being the forte of either of us, thankfully Aviana has the innate skill required to plan for and corral our unique blend of crazy energy. We really didn’t even have a mash bill in mind as we started setting travel and production plans in early to mid-February, it wasn’t until Erik mentioned a book to me (that I then subsequently went on the hunt for) and it arrived at my house in Pekin, Indiana that we had any idea whatsoever of the baseline of the project.

The book ‘Fredrick Heinrich Gelwicks, Shoemaker and Distiller Accounts 1760-83‘ was published by the Pennsylvania German Society and available (although few copies remain) for order through them via mail order. It is mostly made up of merchant account notations and ledgers, but within the pages of the original account (translated from German) was also a pamphlet for setting up a profitable still and several ‘standard’ mash bills of the day. Fredrick Heinrich Gelwicks just so happened to be a distiller in the county of York, just west of Lancaster County, thus, west of the town of Lititz where Stoll & Wolfe is located. Within this pamphlet was a notation for a still beer composed of one bushel of wheat, one bushel of rye, one bushel of rye malt, and three pecks of oats.

Read in modern percentages the mash bill looks like this:

- 21% Malted Rye

- 34% Wheat

- 32% Rye

- 13% Oats

A true ‘Colonial’ mash bill if ever one existed. Also, quite ironic, as I had told Erik if I were coming to PA to distill the product had to be distinctly Pennsylvania rye with a little touch of my ‘Hoosier’ roots and we had even talked of inverting my Spirits of French Lick, Lee Sinclair Bourbon mash bill to make it a rye whiskey with the caveat being that it maintains the 13% oats standard to the original product.

With the mash bill in hand, we turned to the yeast. I felt it was important to bring one of my strains to Pennsylvania for the project, but we wanted something that would make a big, fruity, floral whiskey and ferment quickly as we were working with a limited schedule. As it turns out, my blend of Kveik (Scandinavian farmhouse brewing yeasts) that I had developed over the previous few years fit the bill perfectly. It can ferment at high temperatures and gives strong aromas of dark fruit.

I mailed him the yeast ahead of my arrival along with a cheese culture of Lactic Bacteria to use for souring (a distinctly ‘Black Forest’ culture used to adjust pH during fermentation and increase mouthfeel) which I knew would bring some of my particular element to the project. For the wheat component we decided on soft white wheat as a bit of a pillow for the rye and malted rye while the oats would help thicken the mouthfeel along with the lactic culture. For rye malt we decided on Gambrinus, and of course, the rye, the most important element of all Pennsylvania distilling history had to be special too.

For the rye Erik turned to his cousins, the proprietors of his family’s Kline farm who have been growing Rosen rye for several years. Rosen was once the production rye of both Pennsylvania and Michigan and was used quite widely in Pennsylvania, even historically by Dick Stoll himself. Our good friend Laura Fields (AKA Laura Patruzio online) of the Fields Foundation and the American Whiskey History Facebook page was responsible for resurrecting this beautiful and highly aromatic grain and returning it to the fields, fermenters, and stills of Pennsylvania some years back, a huge win for Pennsylvania distilling history.

As I said, neither I nor Erik are the best of planners, so we only really secured all these ideas about five days before I left for Pennsylvania. Enter Aviana, who saved the day by being the voice of reason and finding the necessary ingredients for such a beast. Make no mistake about it, Aviana is every bit as much a distiller as either Erik or me and can lay a logical road map out for the equivalent of two grown man-children! If not for Aviana I suspect Erik and I might still be talking about what we wanted to do as opposed to actually doing it.

Erik mashed in the first round prior to me arriving, unfortunately (actually quite fortunately) I had misinformed him of the use of the cheese culture which typically goes into the ferment the third day of fermentation, instead he pitched it on day two which caused a lag in the fermentation time, but which developed amazing earthy aromas and the distinct aroma of blood plumbs. We started fermentation at 1.075 and finished out around 1.015 allowing for some of the starchy aromatic components to remain within the distilling matrix.

Erik and his dad Jim got the still up and running with the help of Aviana while explaining to me their unique column still configuration. One of the many reasons for the trip was to learn more about their unique still set up and get some practical time in front of it to compare it to normal low rectification column stills used commonly in Kentucky, and boy is it different. I have maintained a reputation of being a pot still guy (although not a traditional one, as I do love all the bells and whistles) but this column certainly piqued my interest as the methodology and production is quite different from traditional Kentucky columns; the reflux and subsequent proof being determined specifically by the implementation of a doubler with a dephlegmator that works much more like a hybrid pot still with three sieve plates. The flavors and elegance of the distillation at Stoll & Wolfe being readily apparent to any educated distiller as reflective of a unique process, it was a pleasure to see this column still in action.

We Created Modern Day Colonial Alchemical Gold

From the first potable distillate it was readily apparent that we had created Alchemical Gold, not only to our senses, but to the senses of the several who got to try the clear spirit from off the still at a steady 132 proof.

The second mash (which I did get to help with) was treated a little differently. In our haste to get grains ordered I had requested white wheat but had not specified the grade of the grind, as such we were shipped white wheat flour as opposed to whole grain ground wheat. This snafu led to dough balls which Erik had fought with a few days earlier and which he mistakenly hoped I had an answer for. Alas, I did not. As such much was made of breaking these up in the cooker with a metal paddle and later a wooden paddle which Jim Wolfe put together from a last ditch thought on my end and which worked quite suitably. This led to many jokes about the history of PA being principally a rye whiskey state; the water itself not accepting wheat, the water being ‘Gluten Free’.

This second fermentation we kept in the cooker to keep a high level of heat on the mash. My Kveik blend prefers temperatures around 95-105 to pull out fruity esters and to ferment quickly. We added the cheese culture at the appropriate time and a few days later we had a mash that was giving us some beautiful green apple notes.

Not content to simply recreate the ‘Colonial’ turned 20th’ century spirit, turned modern distilling technology with weird yeast experiment we decided to differentiate this run. Paying homage again to my Hoosier roots in what was once known as the Capital of Apple Brandy production, I had worked the previous week to dehydrate a good number of culinary apples. We considered briefly removing the man way from the doubler and hanging these apples in a cheese cloth bag before we decided instead to remove the sight glasses from the plates on the doubler and fill these with the apple slices as a sort of impromptu gin basket. At best I figured given the volume of mash (1,000 gallons) we might have 10-15 gallons of our whiskey actually be flavored via the apple slices, but I was wrong. On a pot still apple slices tend to go a bit “odd” or tailsy in the vapor path on a doubling run as the proof begins to drop from around 158 down to around 120. I always figured this was because the apples were “spent” and had no more to contribute to the flavor and aroma, as it turns out, the elevated 132 proof of the run on Erik’s column still allowed us to extract from the apples substantially more of their quintessence and principal flavor. The entirety of the batch had a unique aroma and tannic structure contributed by the apple slices in a way I had never experienced before. This was evident to everyone present and we were even lucky enough to have Laura on hand that day, as she commented it was the “best white dog I have ever tasted”.

Erik and his dad Jim have collected some amazing history regarding distilling, distilleries, and distilling families in the local area and have compiled several binders’ worth of information that I had a chance to look at. Jim commented that in the early 1800’s there were 183 distilleries in the county and Erik chimed in that one of the neighboring counties had 200 or so. Many of the names were familiar to me from Washington County Indiana, Becks, Becker, Bixler and more.

Wednesday Erik and I headed out to visit some of these old still sites and to collect yeast. I have been collecting yeast from old still sites for years and putting what I find useful into active production every chance I get and as such there was no way I wasn’t going to do the same here. We now had a fantastic mash bill for whiskey we could riff on in several ways including switching out yeast strains. We collected one sample from the Kaufmann Distillery Covered Bridge Area (also relatives of the Wolfe family) and another from near the spring that fed the Becker Distillery. Both are back here with me in Indiana (as is the tradition, take the East to the West) bubbling away nicely on my kitchen table and waiting to be propagated in mass. Once dried I’ll send the yeast back to Erik for another session in May where we’ll use one of the strains for another run, this time potentially packing the doubler plates with dried peaches.

Wrapping Up the Week and Looking Ahead

The week went by quickly and I got to have some great conversations with the folks from Dills Tavern and Elaine Stoll (Dick’s Wife) as well as Dan Black (a follower of mine and Erik’s work), Patrick Leaman, and Jimmy Jaxx from Jimmy Jax Shine Shack. To boot we had an amazing lineup of whiskies to taste from and I got to engage in a short conversation with Ethan Smith about Pennsylvania-Dutch Pow wow Magic.

I had to leave prior to the third cook and distillation but continued to work with Erik via phone to differentiate this cook from the previous two. Breaking a bit with Pennsylvania tradition Erik and I had both noticed the intense aroma of the spent stillage from the first two batches and decided to add some sour mash to the third fermentation to adjust pH and change the flavor profile of the whiskey.

The spirit itself will be proofed down to a low entry of 105 proof and entered into ZAK Cooperage barrels with a #3 char for maturation in the Stoll & Wolfe Barrel Barn. Each batch will be kept separately during maturation but potentially blended in the future. Erik, Aviana, and I discussed the name of the whiskey but have come to no conclusion for the individual “fanciful name” of the product as of yet, but the brand name is tentatively Wolfe & Wilson. It’s a riff on Erik’s heritage as well as that of my mother’s maiden name who came from Pennsylvania to Kentucky and on into Indiana. You see, it’s all coming full circle.

This project was a healing one for me, ten years into my official career, to finally see collaborations as unique as this happen amongst passionate craft distillers who truly care is something special, and the project will continue for years to come. My hope is that this trip is a key to open doors for others in the future. A huge thank you to my new Pennsylvania family and my amazing wife and daughter in Indiana for all the amazing support. Cheers!

Learn more about Stoll & Wolfe Distillery.

Learn more about Spirits of French Lick Distillery.

Learn more about George Washington’s Distillery & Gristmill.

View all U.S. Distilleries.

Book: George Washington’s Gristmill at Mount Vernon – Available in paperback.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.