Buffalo Trace Distillery is a big believer in experimenting. Not only do they have thousands of experiments going on right now but, they’ve put their money where their mouth is and built an entire micro-distillery within Buffalo Trace Distillery. It’s named The Colonel E.H. Taylor, Jr. “OFC” Micro Distillery, complete with cookers, fermenting tanks and a state-of-the-art micro still.

They have ramped up their experiments over the last several years big time. In August 2012 they reported 1,500 experiments. In July 2015 they reported doubling their experiments to some 3,000. Today, they are reporting over 5,000 experiments, a 233% increase in just three years. This sounds like a lot but, at their scale it’s about 1.7% of the 300,000 barrels they have quietly aging in warehouses.

Tell the World or Keep it a Secret Like Colonel Sanders?

Just like a distillers mash bill, some distillers share them openly while others choose to keep them a secret that only a handful of people really know. I applaud Buffalo Trace for sharing their failures. Distillers of all sizes from large distillers to craft distillers to farm distillers can all learn from these experiments. Most of us choose not to talk about our failures, we tend to sweep them under the rug and hope no one will notice. In this case, Buffalo Trace is sharing the results of some of their thousands of whiskey tests and we are all the better for it.

Test, Test, Test

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Here’s a look at a couple of failures, a success story and an ongoing experiment.

1) Buffalo Trace Declares Small Barrel Experiment a Failure

Buffalo Trace started experimenting with small barrels 10 years ago in 2006. They used 5, 10, and 15 gallon barrels each filled with the same mash bill (Buffalo Trace Rye Bourbon Mash #1) around the same time, and aged them side by side in a warehouse for six years.

They said the results were less than stellar. Even though the barrels did age quickly, and picked up the deep color and smokiness from the char and wood, each bourbon yielded less wood sugars than typical from a 53 gallon barrel, resulting in no depth of flavor. The actual bourbon from these tests was never released to the public.

Master Distiller Harlan Wheatley said, “As expected, the smaller 5 gallon barrel aged bourbon faster than the 15 gallon version. However, it’s as if they all bypassed a step in the aging process and just never gained that depth of flavor that we expect from our bourbons. Even though these small barrels did not meet our expectations, we feel it’s important to explore and understand the differences between the use of various barrel sizes.”

Each of the three small barrel bourbons were tasted annually to check on their maturation progress, then left alone to continue aging, hoping the taste would get better with time. Finally, after six years, the team at Buffalo Trace concluded the barrels were not going to taste any better and decided to chalk up the experiment to a lesson learned.

“These barrels were just so smoky and dark, we just confirmed the taste was not going to improve. The largest of the three barrels, the 15 gallon, tasted the best, but it still wasn’t what we would deem as meeting our quality standards. It’s one experiment we are not likely to repeat,” said Wheatley.

2) Buffalo Trace Declares 26 Year Old Bourbon a Failure

In this experiment, Buffalo Trace took bourbon that was poured into the barrel in 1988 and the barrel bore the letters LK, meaning it was produced in Lebanon, KY.

Samples were drawn and the bourbon was evaluated, but this extra-aged whiskey did not meet the taste standards required by Buffalo Trace Distillery to be released to the market. The tasting panel at Buffalo Trace described the bourbon as “vinegary sour, unpleasant, disappointing” and “very bitter and lingering aftertaste.” Sounds delicious right?

3) Buffalo Trace Single Oak Project – And Then There are Successes

The Buffalo Trace Single Oak Project started back in 1999. In this case, they hand-picked and harvested 96 individual oak trees with varying wood grains. Each tree would yield two barrels, one from the top half of the tree and one from the bottom, 192 unique barrels in total.

Unlike the failed experiments, the Single Oak experiment bottles of bourbon did make it to the marketplace.

Seven different variables were studied over the course of the project:

- Recipe (wheat or rye)

- Entry proof (105 proof or 125 proof)

- Stave seasoning (six months or 12 months)

- Grain size (tight, average, or coarse grains)

- Warehouse (concrete floor or wooden rick floor)

- Char level (number three or number four char)

- And tree cut (top or bottom half of the tree)

The winning bourbon was from Barrel #80. It was,

- Rye recipe bourbon

- A barrel made from oak harvested from the bottom half of the tree

- Staves seasoned for 12 months

- Grain size of the wood was considered average

- The barrel received a number four (#4) char inside.

- The whiskey entered the barrel at 125 proof

- Aged in a concrete floor warehouse

- All of the Single Oak Project bourbons were aged for eight years

You can read more about the Single Oak Project and some other experimental releases in these related stories.

Buffalo Trace Distillery Announces the Next Winning Single Oak Project Bourbon

Buffalo Trace Distillery Releases 1st Two Experimental Bourbon Releases of 2015

Buffalo Trace Distillery Tours See a Whopping 190% Increase

4) Buffalo Trace Experimenting with Natural Light

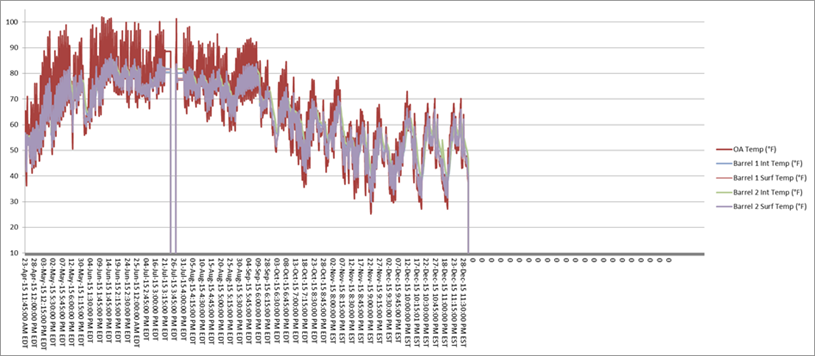

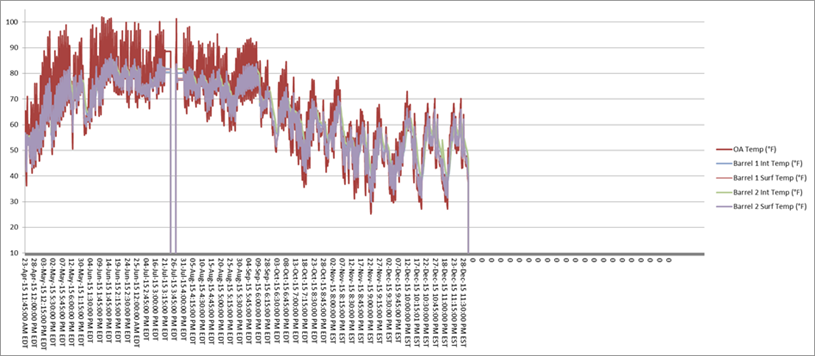

Today, they have an experiment that is about 20 months old. They are testing the effects of natural lighting on aging bourbon barrels. Throughout the year 2015, barrels inside of Warehouse X experienced temperature fluctuations ranging from 30°F to 90°F, along with an extremely high number of humidity variations. This seems like quite a bit of variance, but these environment fluctuations were in fact more mild in comparison to the extreme temperature fluctuation barrels experienced during 2014.

Fluctuations in Temperature

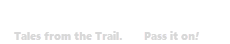

At this point, they have taken several intermittent samples from barrels throughout the warehouse, as well as drawing complete sample sets from all 150 barrels at three different times. This has provided a solid collection of data. They have collected over 50,000 data points for temperature, pressure, humidity, etc. Each sample has been measured on several factors including – color, aroma, proof, taste, and chemical compounds.

Samples have also been reviewed by a small group of tasting panelists to explore aroma, flavor, body, finish, and overall balance. Some of the tasting comments thus far have been “taste of honeydew” and “hints of rich sweetness.”Most intriguing is distinct variations in flavor profile from bourbon between different chambers and the breezeway. This particular experiment is scheduled to be completed in June of 2016.

Early Experiments

Some of the distilleries early experiments focused on aging whiskey in used wine barrels, giving the bourbons chardonnay or zinfandel finishes. It sounds ho-hum now, but in 2007 when these were released, they were considering cutting edge.

Through the years, the experiments evolved in complexity. There have been experiments using non-traditional grains, (rice and oats), various fill proofs, barrels made from woods around the world, and even from forests in the United States not considered traditional barrel producing states. In some of the experiments Buffalo Trace’s own warehouses were the control factors, playing with barrels put up on the same day on different floors and left alone for years, to see how they might taste different. Or how a concrete floor warehouse and a wooden floor warehouse affect the taste of a barrel of bourbon, which one is better?

Regardless of the size of your distillery business, it’s important to continue to test, listen to your customers, listen to your employees, learn from your mistakes, celebrate the successes and never stop dreaming.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Like us on Facebook and Follow us on Twitter.