Few drinks in history can claim a past with as much conflict and decadence as that of gin. A spirit produced on every continent and enjoyed by millions daily in all corners of the globe. Evolving from plague into war, carried across seas inciting epidemic or fueling Navy’s and colonists worldwide – this is the story of gin.

“[gin] charms the unactive, the desperate and crazy of either sex, and makes the starving sot behold his rags and nakedness with stupid indolence. It is a fiery lake that sets the brain in flame, burns up the entrails, and scorches every part within; and, at the same time, a Lethe of oblivion, in which the wretch immersed drowns”.

Related Stories

Part 1: The History of Gin – Conflict and Decadence

Part 2: The History of Gin – The Boom and Drunken Bust

Part 3: The History of Gin – From Debauchery to Modern Day Decadence

His observations, while rich in persecution, were written at the beginning of an era in England known by historians as the Gin Craze. An era which would see Mandevilles verbose description become an all too accurate reality. But the story of gin does not begin here, but with its namesake.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

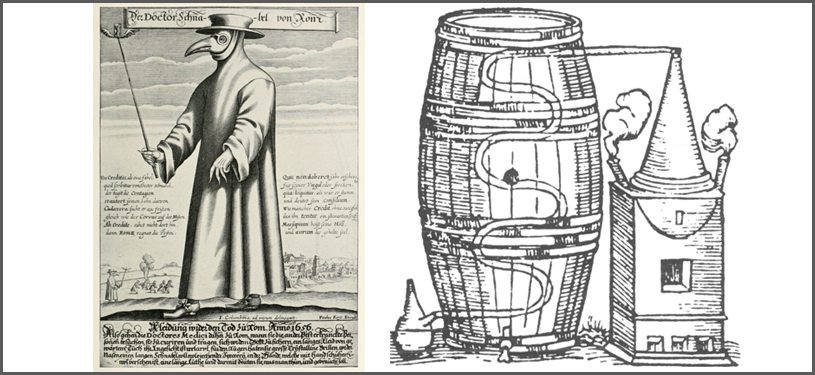

Early Dutch pot still taken from Een Constelijck Distilleer Boeck by Philippus Hermanni -1552. The first printed recipe for a juniper-infused distillate.

The earliest we begin to see any juniper based distillates is in 13th century Flanders (present day Dutch speaking northern Belgium) with a spirit accurately named Jenever [juh-nee-ver]. Flanders was an influential province during the Middle Ages with the city of Bruges playing a central role in the culture and trade of the region. Jenever during these early periods was more a juniper infused brandy than the herbal distillate we associate today. With evidence of distillation practiced as early as 450 BC, the Dutch became the masters of the process in central Europe since the 1100s where it was employed as a method of saving money on the exportation of wine. By using distillation merchants payed less tax on volume as the wine could be reduced through distillation prior to shipping and re-hydrated at the port of destination with no spoilage. Known as brandewijn (etymology of the word brandy) literally meaning “burnt wine”, Dutch spirits whether infused or distilled with fruits, botanicals or cereals, shared this common name for all distilled liquors up until the 19th century. As such, it is difficult to accurately define the earliest juniper distilled spirit yet not difficult to imagine the practice with such a long history use for both juniper and distillation in Europe.

Copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel (a.k.a. Dr. Beak), a Roman plague doctor with juniper filled mask – 1656. Also known as the origin of “The Quack.”

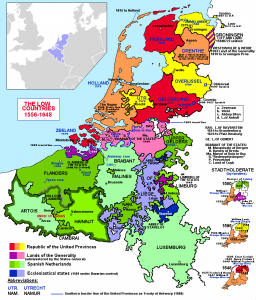

Initially built of a feudal collection of tribes from both Germanic, Frankish and Belgic origins in the 4th century AD, the region which encompassed old Flanders was known as the Low Countries and consisted of modern day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxemburg and parts of northern France and western Germany. The Low Countries comprised of a collection of seventeen fiefdoms continually pulled between the powers of the Holy Roman Empire to the north and east, and the Kingdom of France to the south. By the time the plague hit the area in 1349, everyone was desperate for a cure and Juniper, already established as the provincial go-to cure-all, was look to for the solution. Also known as the Black Death or Great Plague, infection was believed to be spread by the inhalation of the disease and as such, a widely published Plague Treatise advised people to burn juniper branches at least twice a day in their home to “protect against the epidemic”. Duck billed masks filled with crushed juniper berries became part of the ensemble of the common doctor of the period to protect against the plague as much as mask the smell of putrescence. The term quack which used today to define an incompetent physician or fake remedy, came about from this striking visualization made by these doctors with beaked masks and dark coats as well as their near inability to cure anything let alone the plague. Unfortunately for the ill-informed populous of 14th century Europe, it was the flea which carried the disease on the back of the many rats residing in European capitals and therefore nothing juniper could influence – unless all the rats were pregnant in which case the ingestion of juniper in rodents can cause miscarriage…but what are the odds?

Reaching it’s peak during the 1348-50s, it is estimated that the Great Plague killed an enormous 30-60% of Europe’s total population and despite such heavy tolls, juniper was believed the solution throughout. By 1482 and with European populations returning, the Low Countries became united for the first time under the House of Hapsburg (rulers of the Holy Roman Empire for 300 years), instigating events which would unwittingly pave the way for a new and independent Dutch nation as well as introducing jenever to their cross-channel partners, the English.

In 1568, The Eighty Years’ War between the provinces of the Low Countries and King Phillip II of Spain (a member of the Hapsburg rule) began bringing with it a uniting of the seventeen provinces (click map to enlarge) under the Union of Utrecht pact to depose Spanish control and giving birth two years later to The Netherlands (translated from the name neder “lower” and landt “country”). Vitally, this new pact also helped gain sympathy from Queen Elizabeth I of England who four years later joined the conflict against Spain, sending English naval and military forces to aid the new nation. It is believed that during this period of English involvement, men of the English navy were introduced to jenever for the first time (writing it for the English pronunciation genever) during the battle of Antwerp circa 1570. More notably was the mean in which it was used by Dutch soldiers and sailors who were recorded imbibing the local spirit prior to heading into battle to help steel themselves. From this action we gained the popular English phrase “Dutch Courage” to describe any alcohol fueled confidence boost. As translated from an old Dutch saying “A sailors best working compass is a glass completely full of genever”. By 1585 the Spanish won a major victory, successfully capturing the largest and most culturally influential city in The Lowlands – Antwerp. As a result, over half the city’s population (around 60,000 people) fled either north to Flanders or across the Channel to allied England, bringing with them their beloved distillation techniques and love of juniper.

Emblem of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie)

By the start of the 17th century, Europe was at the beginning of a global explosion driven on the back of powerful merchant conglomerates and a period known as the Spice Race. Over the next century, the Dutch East and West India Companies (V.O.C. and G.W.C. respectively) emerged as new super powers on the back of their huge trading might. Driven by coffee and sugar in the west and spice in the east, a Dutch merchant and navy man’s affinity for genever was now spread globally. Due to its popularity amongst sailors, genever producers began infusing further spices and herbs into their spirits to aid the sailors poor diets during long voyages. One popular ingredient was the perennial herb known as scurvy-grass (Cochlearia) whose leaves hold naturally high levels of Vitamin C. First used in 1730, the infusion of this plant into genever predated the common knowledge that Vitamin C held the cure for scurvy, by almost six decades. A commonly quoted gin misnomer is that of Doctor Sylvius Cornelius as the acclaimed “Father of Gin”. Credited with the spirits invention thanks to well documented distribution of juniper tonics from the University of Leiden between 1658 and 1672, the Nationaal Jenevermuseum Hassalt in Belgium has rebutted this fact with evidence aplenty of juniper spirits in production almost 400 years prior to his involvement. Our satirical socialist Bernard Mandeville, would conclude it best when contradicting his ruinous observations of gin by stating that as it;

“caused some, so it cured others…by upholding the courage of soldiers, and animating the sailors to the combat; in the two last wars no considerable victory had been obtained without”.

But Mandeville was yet to experience the true meaning of the expression “Mothers Ruin”. By the beginning of the 18th century, gin had made its way into common English society on the back of popular Strong Water Shops and Coffee Houses. What followed however would be regarded as one of the darkest periods in modern English history with gin, at its very heart, playing the role of both muse and devil.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Like us on Facebook and Follow us on Twitter.

References

- Gin: A Global History, Lesley Jacobs Solmonson, 2012

- The Fable Of The BeesOr Private Vices Publick Benefits, Bernard Mandeville – 1714

- TNAP: Database of the VOC Documents– 1602-1795

- Koninklijke Bibliotheek: National Library of the Netherlands, “Der Naturen Bloeme” – 1350

- The Rise of the Dutch Republic: III, John Lothrop Motley- 1855

- A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. Suzanne Austin Alchon – 2003

- Nationaal Jevevermuseum Hasselt

- Cor Snabel’s and Willem’s Old Dutch Measurements