From its discovery by the English during the Dutch War of Independence, Gin’s evolutionary journey had seen England plunge into social degeneracy on the back of Madam Geneva’s ruinous ways. But from the bottom the only way is up and thanks to time well spent in legislative rehab, gin would be reborn a new spirit.

The hammer finally came down on England’s debauched addiction to gin thanks to the Gin Act of 1736. It was the eighth legislative attempt at regulating the alcoholic epidemic. The success of its predecessors lay in a combination of; the raising of licensing fees to the impossible price of £50 ($65 US, a lot in those days), the imposing of a hefty fine and two months imprisonment for any private distillers, the financial incentivizing of people to inform on any illegal stills and most importantly, supplying the men on the ground to enforce these schemes.

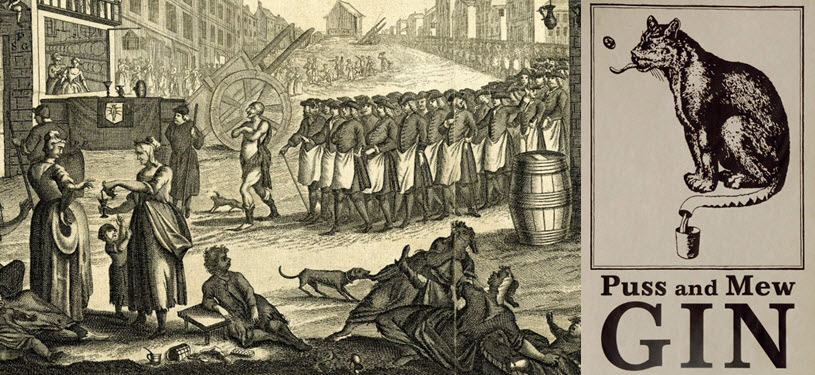

Recognizing the change for what it was – a final end to the reign of Geneva – people took to the streets in riot. Gin shops hung black cloths over their signs in mourning and groups of people hosted mock funeral processions throughout England in lament at The Death of Madam Geneva. But as with most cases of prohibition, gin merely went underground. Her days as Madam Geneva may have been at an end but not her spirit, instead she became reincarnated as a cat – a Tomcat to be precise.

The Funeral March of Madam Geneva

The Funeral March of Madam Geneva by John Bowles – 1751. The print shows the mock funeral procession of Madam Geneva by citizens of the St Giles slums, London

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

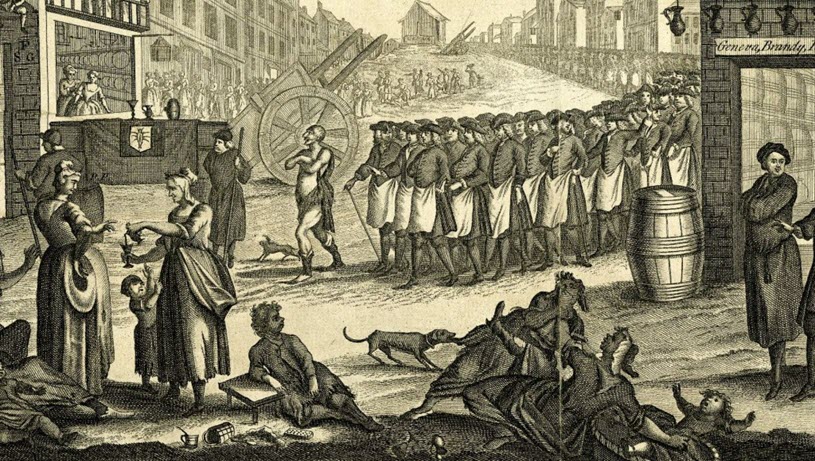

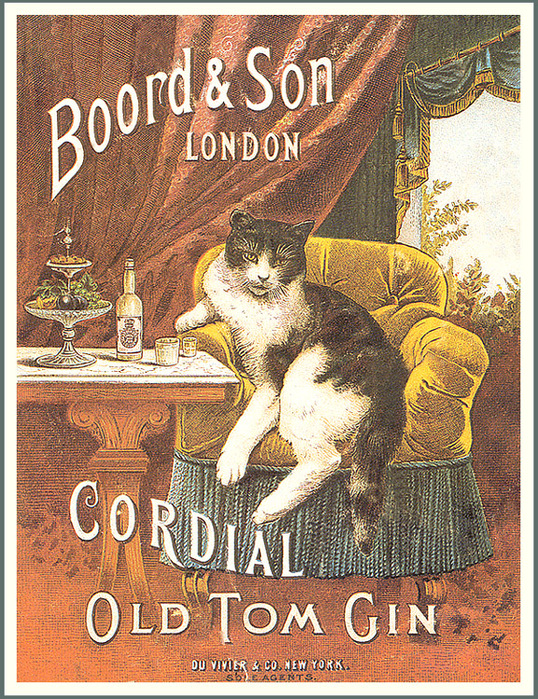

While the new act influenced the first successful decline in gin consumption in almost 50 years, it was still a long way from control. Due to the closure of so many public gin shops and distilleries, customers merely turned to their local black market retailer where a new popular style of gin became affectionately known as Old Tom. While there are many stories surrounding the etymology of Old Tom, common credit lies with an Irish informer turned illicit distiller and retailer named Captain Dudley Bradstreet who published his exploits in a book entitled, The Life and Uncommon Adventures of Captain Dudley Bradstreet – 1755. Dudley’s life is indeed worthy of a book with a resume that covers his time as an Army Captain, government spy, criminal, entrepreneur, brewer and playwright – but it is Dudley’s dabblings in the world of illicit gin sales that interests us most. In his autobiography Dudley writes; “My first Scheme [sic] I went upon was directly opposite to the Laws of England“. Beginning with a purchased copy of the aforementioned Gin Act, Dudley set about finding a means of retailing gin outside of the constraints of current legislation. Contriving a plan, Dudley acquired – with the help of a sponsor – a quiet venue in Blue Anchor Alley, St. Luke’s Parish, London (behind the Barbican, Islington) where he;

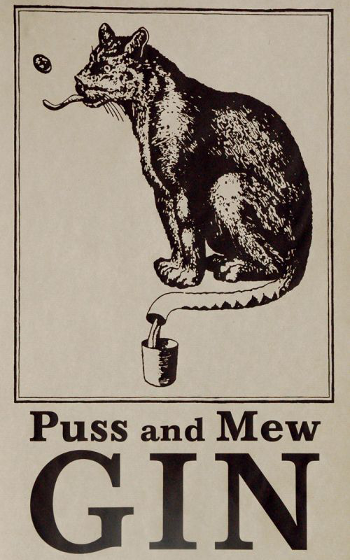

“…purchased in Moorfields the Sign [sic] of a Cat, and had it nailed to a Street Window; I then caused a Leaden Pipe, the small End out about an Inch, to be placed under the Paw of the Cat; the End that was within had a Funnel to it”.

Related Stories

Part 1: The History of Gin – Conflict and Decadence

Part 2: The History of Gin – The Boom and Drunken Bust

Part 3: The History of Gin – From Debauchery to Modern Day Decadence

With the site and sign in place Dudley purchased 13 pounds worth of credible gin from a “Mr. L—dale in Holbourn” ready for sale and opened what would become known as the first Puss & Mew Shop. Identifiable by his cat window, patrons would knock on the door and whisper through a slot, “Puss, give me two pennyworth of gin” to which the reply would be “Mew” if there was any gin to sell. Coins would be distributed through a hole in the cat’s mouth with the gin dispensed via the funnel and lead tube under the cats paw – basically the first rudimentary vending machine. Dudley continues to write;

“From all Parts [sic] of London People used to resort to me in such Numbers, that my Neighbors could scarcely get in or out of their Houses”.

Puss and Mew

The ritual became copied throughout London’s back streets and a new gin ritual was born. Generally these shops were dispensers only with the liquor being produced offsite in case of a bust, at which point the occupants would bundle out a window or back door.

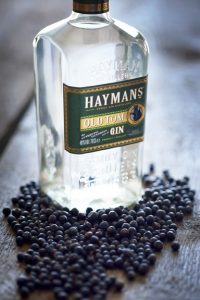

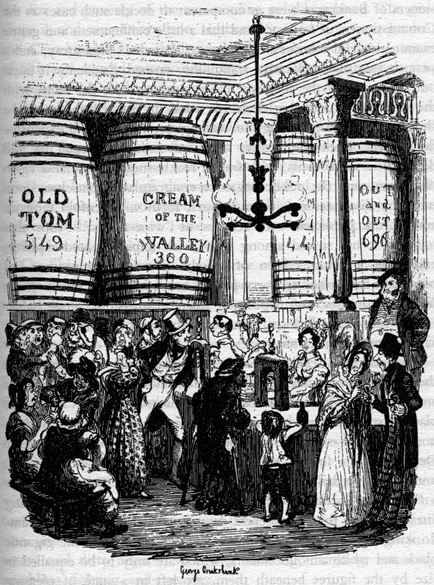

Despite high licensing fees and taxes imposed by the 1736 Gin Act, by 1750 there were a recorded 29,000 licensed gin retailers across England – one can only speculate how many further unlicensed shops existed. While general social standards had improved inside gin shops since the common debauchery of the Gin Epidemic, many had not. It was still often safer to drink gin than water and as such it was still normal to see children drinking and drunk, alongside adult patrons. By the time legislation was finally relaxed in 1760, Old Tom came out of his back alley and into the mainstream where the spit-and-sawdust venues of old had evolved into slightly more sophisticated gin joints thanks to the social standards set by the coffee house revolution.

The Gin Shop by George Cruikshank, c.1731

In 1660 England officially inaugurated their battle fleet as the new Royal Navy and with the VOC (Dutch East India Company) dominating trade with the Spiceries of the East Indies, their relationship with England had become sour to say the least. Just 21 years before William of Orange III ascended to the English throne, the Second Anglo-Dutch War between the naval might of both England and The Netherlands, had come to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Breda in 1667. At the heart of this second conflict lay two islands – The British held, nutmeg rich island of Run in the Banda Islands, Indonesia and the emerging Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in the colonial Americas. Both islands had been forcibly taken by their opposites and held in near equal worth to each other. While nutmeg at this time was equitable to more than its weight in gold, New Amsterdam (renamed New York after the Duke of York who would later become King James II) would become one of the world’s great capital cities, so who got the better deal?

New Amsterdam (New York)

First settled by the Dutch in 1624, New Amsterdam was invaded and taken by the English forty years later at a time when it held a population of around 270 – a tad shy of the 8.3 million living there today. Impressively, this early Dutch influence can still be easily found throughout the New York area today from the colors of the city’s flag representing that of the Netherlands, to the many state landmarks whose names derive from the early Dutch settlers such as – Brooklyn (Breukelen, Dutch town), Bronx (Bronck, named after the first Dutch settler to the area), Harlem (Nieuw Haarlem, Dutch city) and Coney Island (Konijneneiland meaning “Rabbits Island”) to name just a few. Even the popular American moniker Yankee is believed to derive from these Dutch roots. One explanation dates its use from a combination of the two most common Dutch colonial names at the time – Jan (“John”) and Kees (“Cornelius”) [For further reading see Manhattan: The Island of General Intoxication]. New York was even briefly retaken by the Dutch in 1673 during the Third Anglo-Dutch War where the area was again renamed, this time New Orange but after holding it for only a year it was once again relinquished to the English and reinstated as New York.

Back to the Gin

Bringing the story back to gin; along with control of a lucrative beaver fur trade, the old Dutch colony also;

“…came with a number of pot stills from which the Dutch colonists had been distilling grain brandewijn [brandy wine]“.

If the Dutch – having records of distilling on Manhattan since 1640 – were using traditional corn wash as was common in the manufacture of early brandies and jenever (later spelled genever), this would mean the Dutch were the earliest recorded whiskey distillers in America.

Thanks to the expansive might of the Royal Navy throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, gin distillers such as Gordon & Co. (est. 1769) were able to spread their products throughout the developing empire with relative ease. Plymouth Gin (est. 1850) was, and still is, a major player in the life of the average English sailor in part due to their location near the Royal Navy’s Devonport Dockyard in Plymouth. Plymouth distillery secured their naval association early on by releasing a Navy Strength Gin (57% ABV / 114 proof) in 1793. With onboard naval rations of the time commonly stored in a ships hold near barrels of gun powder, the increased level of alcohol in the spirit ensured that if gunpowder was soaked by gin during engagements it would still ignite due to the high levels of alcohol in the spirit. This same reaction is said to be used as a means of proof by Naval Pursers to test the correct dilution level of overproof rums before serving to crew during their twice daily rationing. A spirit of around 100 proof (50% abv) would reputedly still ignite gunpowder with anything less removing its ability to spark – although this humble writer is still awaiting the chance to try it out!

Dominican Black Friars Distillery – Plymouth Gin

While the British navy was allocating a heady half pint of rum to their sailors each day, the Dutch were even more generous. A Dutch order in 1864 called all chartered ships to ration out; “For European, African and Ambonese non-commissioned officers and troops, and for European women; the morning 0.075 Dutch kan [about 105ml or 3.7oz] of Jenever; in the afternoon 0.075 Dutch kan of Jenever; in the evening 0.075 Dutch kan of Jenever”. Equatable to one fifth of a bottle of overproof gin per person, per day. Sailors would line up and one after the other and handed a cup filled with genever by an officer to the correct measure, before being downed in one and passed on.

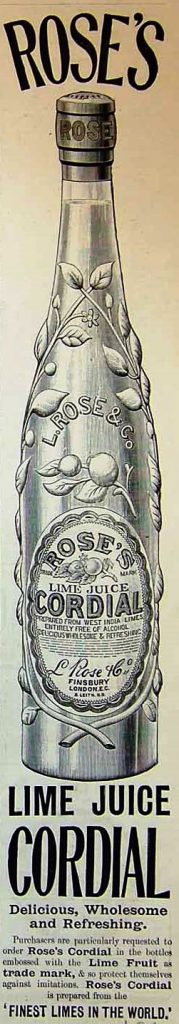

In 1870, Schweppes Indian Tonic Water was created to disguise the unpleasant taste of the quinine necessary to fight malaria in the tropics. It arrived in London and was mixed with the emerging style of dry London gins to create the first commercial “G&Ts” – Gin & Tonics. That same year would also see famous English author Charles Dickens pass away at the age of 58 at Gads Hill Place in Kent leaving behind a large collection of liquor casks and around 2,160 bottles of wine, spirits and cordials; of which included “3 dozen Cordial Gin” and “16 bottles of Hollanche Genever Hoboken (dieBie & Tarlay)”. The whole collection was auctioned off for five hundred and twenty one pounds, seventeen shillings and sixpence. Dickens, a keen mixologist, also left records detailing his own punch recipes; many of which reflect an equal preference for English and Dutch gins alike.

The final step in the journey of gin from plague through revolution and debauchery to modern-day decadence, is the development of the continuous or column still. From the original patent by Jean-Baptiste Cellier Blumenthal in 1813 Belgium to the much improved design by Aeneas Coffey in 1830, the column still vastly improved the quality of manufactured distillates. Due to his previous role as Inspector General of Excise in Ireland, Aeneas Coffey was perfectly placed to improve on traditional still designs due to his many frequent visits to distilleries on behalf of the tax man. The Coffey Still as it became known not only saved manufacturers time and money due to its continual process but also gave them the ability to rectify spirits at a higher purity removing many of the common esters and mal piquancy which was previously masked by the sweetening of Old Tom gins. A spirit which was generally only “…aged about the time it takes to get from the bathroom where it is made to the front porch where the cocktail is in progress”.

Coffee Still, Kilbeggan Distillery

From this new cleaner distillation process evolved a gin that was well balanced for the first time between the aromatic qualities of juniper and it’s spicy botanicals. Gin had finally become a premium spirit and as such England had created its own unique style and just in time for the next social revolution – the cocktail. The Gin…Fizz, Fix, Flip, Crusta, Daisy, Punch, Julep, Sling, Sour and Smash are just some of the recipes listed in the earliest printed cocktail book by Jerry Thomas in 1862.

Sipsmith Independent Distillers – Artisanal Gin

Before you had drunk your first G&T, T&T, Martini, Pink Gin or Gin Punch – the juniper flavored spirit had already survived plague, war, depression, colonisation and helped develop the first cocktails. Whether known by the name Jenever, Mothers Ruin, Old Tom or Madam Geneva – we love it, we’ve always loved it and long may we enjoy it.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

References

- Bols UK Brand Ambassador– John Clay

- Gin: A Global History. Lesley Jacobs Solmonson, 2012

- Gin: The Much Lamented Death of Madam Geneva –The Eighteenth Century Gin Craze. Patrick Dillon, 2004

- Convivial Dickens: The Drinks of Dickens and his Times.Edward W. Hewett & W. J. Axton, 1983

- Google Books: The Life and Uncommon Adventures of Captain Dudley Bradstreet.Dudley Bradstreet, 1755

- World Wide Words: Investigating the English Language Across the Globe

- Diffords Guide: Inner Geek, Old Tom Gin– Industry Magazine

- Internet Archive:Reports of patent, design, and trade mark cases

- Haymans Family Gin Distillers, London

- Sipsmith Independant Spirits, London