Since its founding in 1953 Maker’s Mark Distillery in Loretto, Kentucky has been a company that is well known for ‘sticking to its knitting’. They don’t wander off the Maker’s path too far. They make one thing and they make it really well, a wheated Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey.

The way the story goes when Maker’s Mark started out Bill Samuels, Sr. took the family’s original 170 year old bourbon recipe and burned it. From there he started on a quest to make a smooth and approachable bourbon with an easy finish – a true contrast to hot, harsh whiskies of the past that as Bill Samuels, Jr. said wouldn’t “blow your ears off.” Now, just over half a century later they are still making the same bourbon with the same recipe and same process that Bill, Sr. and Margie pioneered 59 years ago.

Maker’s Mark DNA Project – Barrel Entry Proof Experiment

In the spirit of innovation, Maker’s Mark has launched the DNA Project. This is a series of experiments that will dive into variations in fermentation, distillation and maturation, all in an effort to better understand the science – and the motivation – behind Bill and Margie Samuels original taste vision. First up for the DNA Project is the Maker’s Mark Barrel Entry Proof experiment. The goal for this experiment was to see just how much impact barrel entry proof has on the taste profile of bourbon.

“I’ve got to be honest,” said Maker’s Mark Director of Innovation Jane Bowie. “This is probably the most excited I’ve ever been on any project I’ve personally gotten to be a part of. I think just the learning makes it exciting.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for the Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

“At Maker’s, we make one thing. It comes off the still at 130 proof and it enters the barrel at 110. With this experiment we took that 130 and we took it to the cistern and we actually hand cut it down [to 110, 115, 120 and 125]. Then we filled 25 barrels at each proof for the test.

“Our role in innovation is to study flavor levers. We always think the job is to spend 40% of our time studying agriculture and where flavor comes from. And we probably spend another 40% studying processes. Why does it matter? People want to make it very linear and it’s not. People often ask what percentage do you think yeast gives? And it doesn’t really work that way.

“‘What’s this choice, what does this particular lever do?’ We are leaving a lot of money on the table by not going into the barrel at 125 proof. So for this experiment we decided to bottle 15 of those 25 barrels to share. The findings are fascinating. We are leaving the remaining 10 barrels to keep studying the role of entry proof in maturation. We always knew there was a correlation and now we know.”

In the 19th century there really were no hard and fast rules on what a bourbon’s barrel entry proof should be. If we look at the history of bourbon in the early days bourbon was mostly distributed in barrels so it was not uncommon to have a barrel entry proof between 90 to 103. This made for a palatable bourbon right out of the barrel for consumers.

During a tasting for the Maker’s DNA Project whiskey historian Mike Veach helped to put barrel entry proof into perspective.

“It all started in the 19th century. In the 19th century distillers did not bottle their own whiskey,” explained Veach. “They sold their whiskey by the barrel to a saloon or a liquor store and people would come in with their own bottle or flask and fill it right from the barrel because bottles were expensive. They all had to be hand blown. It wasn’t economically feasible for a distillery to do. So what they did is they put the whiskey into the barrel at a proof that people could drink. Somewhere between 90 and 105. And that was the barrel entry proof throughout most of the 19th century and even up until the 1950s.

“Barrel entry proof stayed that way through Prohibition but then in 1934 when they redid the regulations they actually put a maximum entry proof of 110. And it remained 110 until 1962.”

When Maker’s Mark started distilling in 1954 they entered the barrel at 110 proof. In 1962 the U.S. government modified the whiskey making rules and increased the maximum barrel entry proof from 110 to 125 proof. The higher entry proof allows a distillery to get more net volume out of each barrel as they can add fresh (un-aged) water to get the bourbon down to a bottling proof of say 90 proof.

Some distillers upped their entry proof right away when the law changed but most stuck with the lower proof for many, many years. In the case of Maker’s Mark, they never changed it when the law changed, they continued to enter the barrel at 110 proof until this DNA Project Experiment.

Maker’s Mark Enters the Barrel at 110, 115, 120 and 125

Back in 2013 Maker’s ran an experiment to test the effects of entering the barrel at four different proofs. All other elements were kept the same. Maker’s took 100 barrels of bourbon and split them into four groups. There were 25 barrels of 110 proof, the Maker’s standard, 25 barrels at 115 proof, 25 barrels at 120 proof and 25 barrels at 125 proof, the maximum allowed by law for a bourbon.

To keep the variables to a minimum everything else was kept the same. They were standard Maker’s barrels made from 9-12 month air dried staves made with a #3 char. The barrels were not toasted because that’s simply not a standard part of the bourbon making recipe for Maker’s (Perhaps we’ll hear about a non-toasted vs. toasted barrel DNA Project test in the future.)

Test Barrels Were Not Rotated

Each barrel was produced from the same cistern and placed in the same warehouse floor and left to mature for nearly eight years.

The barrels for this test were not rotated. Maker’s is one of the few large distilleries that actually rotates their barrels. This helps to ensure a consistent flavor profile with each finished barrel. They normally place new make barrels in the upper ricks of the barrel warehouse. The upper portion of the rickhouse can reach 105 degrees in the summer months. They remain there for at least three summers and then they are moved to the lower levels of the warehouse until they are ready for bottling after 5 to 7 years. The lower levels tend to have an average temperature of 78 degrees in the summer. Barrels in the middle floor of the warehouse are not rotated.

For this DNA Project these 100 barrels were placed in the middle floor of Warehouse 30 in downtown Loretto and they were not rotated in order to remove the location variable from the test.

The Results: How Did Barrel Entry Proof Affect the Bourbon?

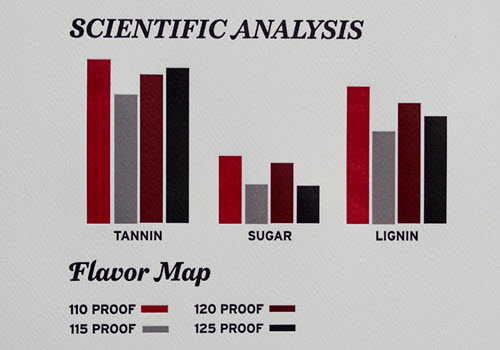

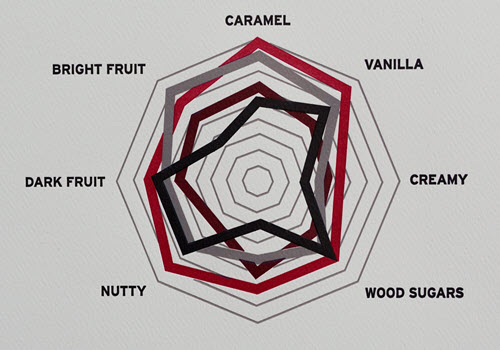

The short answer is there were no bad results, they were each just different. The test results show the lower proof bourbon was higher in tannin, sugar and lignin. As you can see from the spider chart those tend to bring out flavors like caramel, vanilla, dark fruit and nutty. While the higher barrel entry proof at 125 is much lower in caramel, bright fruit, and nutty flavor.

The barrel entry proof does indeed have a pronounced effect on taste profile because each of these bourbons showcases a flavor all its own. And while these new whiskies are distinctive enough to stand on their own the higher barrel entry proof didn’t necessarily taste like what you would expect from Maker’s. What this test did do is affirm that Bill and Margie’s original taste vision of entering the barrel at 110 proof still stands to this day.

Maker’s Fans Can Purchase These Experimental Bottles at 110, 115, 120 or 125 Proof

Unlike a lot of experiments that bourbon fans can only read about these particular barrels have actually been bottled and will be available beginning September 15, 2021 at the distillery and select Kentucky retailers. This DNA Project netted out 2,400 sets of Entry Proof, meaning 9,600 bottles all together.

These barrels were all bottled at barrel strength. Here is their final proof for each test group.

| Barrel Entry Proof | Final Bottle Proof |

|---|---|

| 110° | 116.0° |

| 115° | 117.1° |

| 120° | 122.3° |

| 125° | 125.4° |

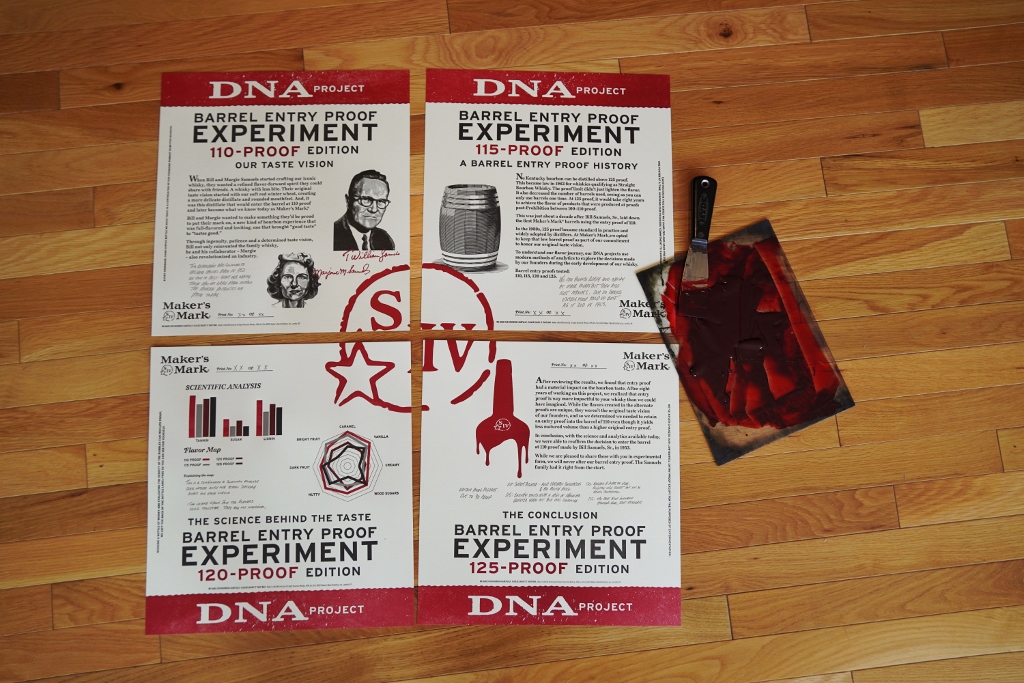

Each bottle will be sold with its own custom-pressed, hand-numbered collectible poster from Louisville’s Hound Dog Press, highlighting experiment notes from the Maker’s team. All four posters combine to create a larger display piece, perfect for the Maker’s Mark fan.

Each Maker’s Mark DNA Project bottle has a suggested retail price of $99.99.

There are 10 each of the test barrels left over for additional aging. Time will tell if these additional 40 barrels make it to the market one day.

Learn more about Maker’s Mark Distillery.

View all Bardstown and Nelson County Distilleries.

View all Kentucky Distilleries.

View all U.S. Distilleries.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.