![Why is the U.S. Alcohol Market So, So Complex [BrandScape]](https://www.distillerytrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/why-is-the-u.s.-alcohol-market-so-so-complex-brandscape.jpg)

I’m often asked, “How come the US alcohol market is so complicated?” Distillers, importers, retailers, brand owners, wholesalers, marketers, consumers: everyone finds it complicated. There are states where their government controls wholesale (and, sometimes, retail, or retail is contracted, or retail is contracted and privatized), states where wholesalers have exclusive monopolies on brands, some states are split into non-overlapping regions (where the sale of alcohol is privatized, or controlled by the state, or controlled by the state with older private-stores grandfathered in), rules for marketing vary, taxes are different, some municipalities completely outlaw alcohol, while others dictate what beverages can be sold – and their proof. Yes, it’s complicated. The United States functions like fifty separate countries – more, in fact. “How come it’s so complicated?” is an inevitable question.

In reality, how we got here was an accident. Maybe accident is too strong a word, or implies too much randomness. What I mean is that the current system was not planned. Or at least not planned by a government task-force or committee that, through research and contemplation, set a foundation for what might be best for the US overall. It was the outcome of one man’s passion for social reform and his private investment in trying to understand how one could responsibly balance the sale of alcohol against the run-away ills of a market where only profit mattered.

American Spirits Exchange is a national distributor and importer serving the alcoholic beverage industry including distilled spirits, wine and beer. Learn More Here…

The Four Key Documents that Got Us Here

- The 18th Amendment

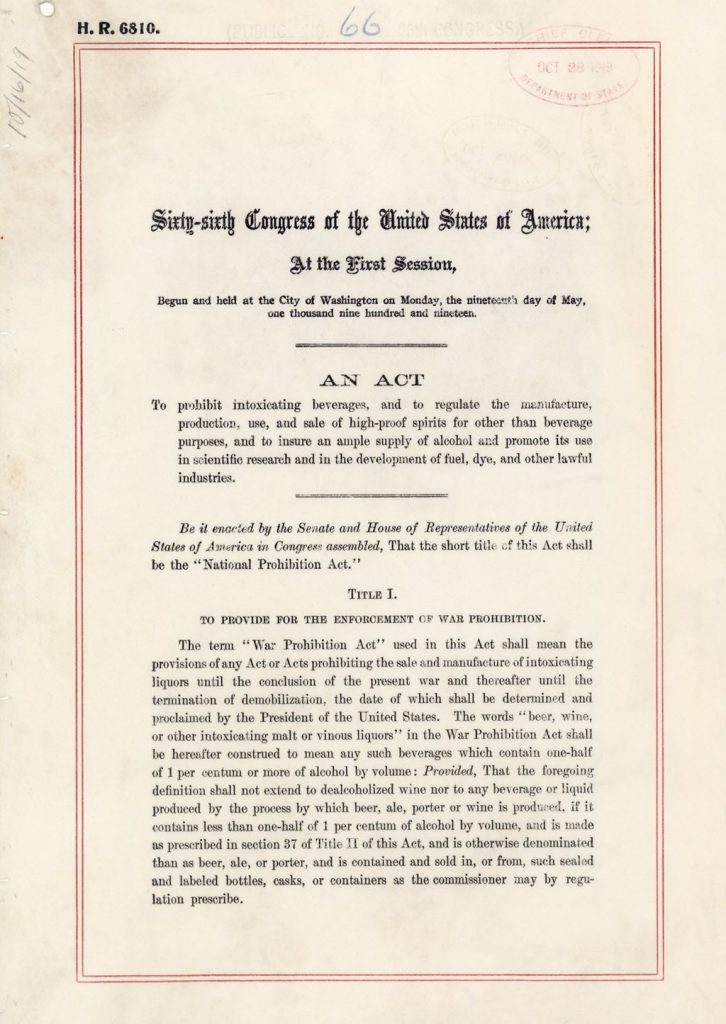

- The Volstead Act

- The 21st Amendment

- Toward Liquor Control

The full text of the 18th Amendment, The Volstead Act and the 21st Amendment are included below. Interestingly, we can’t share the Toward Liquor Control document because it was written by two private citizens and is copyrighted to this day.

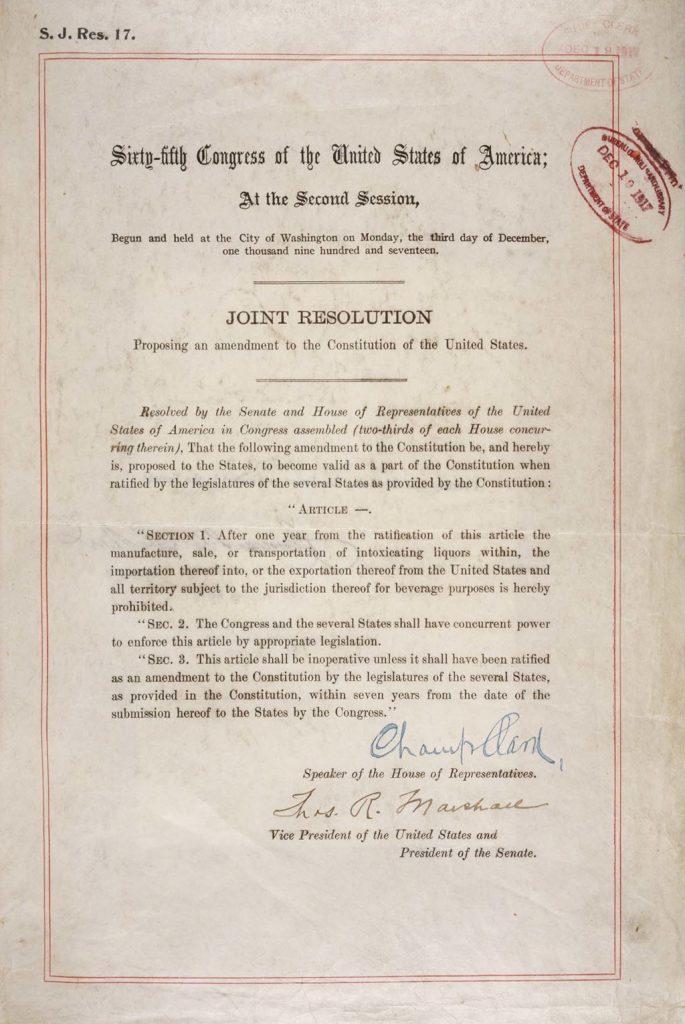

The 18th Amendment – Prohibition and National Abstinence

John D. Rockefeller Jr. was a life-long teetotaler, as was his father, and his father before him. Ardent in his opinions, he believed that complete abstinence from “intoxicating liquors” was the best choice for society and individuals. And, he was willing to put his political clout, and extensive finances, behind his convictions as an early supporter, and financial angel, of the Anti Saloon League, an emerging lobbying-effort that would culminate in the 18th Amendment, ushering in national Prohibition. The buildup to national Prohibition was long coming. For decades, the US struggled in fits and starts with various temperance movements. Many local governments had already moved to prohibit alcohol in their communities, and by the time the 18th Amendment was ratified in 1919 most states had already banned some part of alcohol beverage commerce.

U.S. Constitution – The 18th Amendment

SECTION 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

SEC. 2. The Congress and the several states shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

SEC. 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several states, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the states by the Congress.

But moving from local-option Prohibition to national abstinence proved challenging. Over the course of a decade the problems Prohibition created seemed to outweigh the initial promises. As the 1920s drew to a close, and Americans started to feel the early tremors of the great depression, the grumblings for repeal grew louder. Rockefeller, thoughtful and savvy, realized that the “social good” suffered more under the 18th Amendment than it benefited. Ever the pragmatist, he pivoted, “Therefore, as I sought to support total abstinence when its achievement seemed possible, so now, and with equal vigor, I would support temperance.”1 American legislators would soon be faced with a challenge more daunting then policing Prohibition: how to enact temperance.

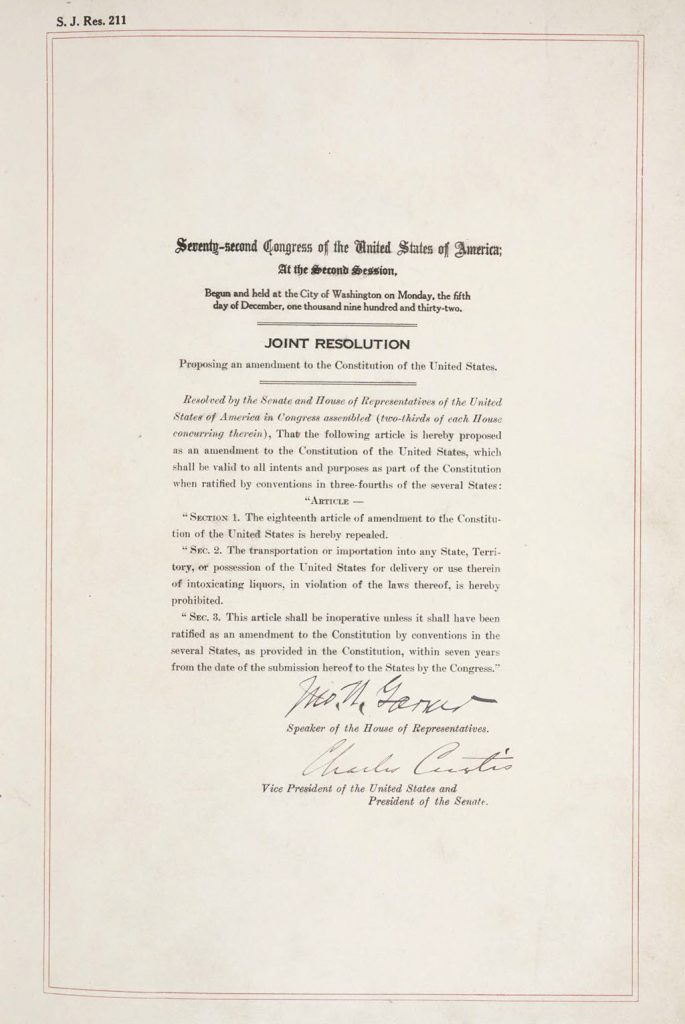

The 21st Amendment – Grants States the Right to Control Alcohol

On February 16, 1933 the US Senate passed a resolution for the repeal of the 18th Amendment; immediately following, on the 20th, it was also passed by the House of Representatives. It was then up to the states: Utah became the final state needed for ratification on December 5, 1933. The new constitutional amendment – the 21st – is concise, containing just two clauses.

- The first repeals the 18th Amendment

- The second gives states the power to regulate alcohol commerce within their borders.

The latter point an essential concession to Prohibition-friendly states and a growing movement toward more localized government. What had been a federal problem of enforcement now became a state problem of implementation. How do you regulate the sale of intoxicating beverages within your borders? The states were given the power, but they had to find, or invent, their own tools to harness and direct it.

U.S. Constitution – The 21st Amendment

SECTION 1. The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

SEC. 2. The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

SEC. 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by conventions in the several states, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the states by the Congress.

The Road from Complete Restriction to Temperance

Prescient, as usual, Rockefeller saw the potential dilemma on repeal’s horizon. As a humanitarian he was concerned for society’s welfare, as a financial giant he recognized the power of market dynamics focused on profitability. Completely restricting alcohol did not work, but if the market for alcohol was completely unregulated, then unscrupulous profiteers could benefit at the expense of individuals, and ultimately society. How then can one use the law to offer alcohol for sale, but change the equation in order to reduce or remove the drive to only maximize profits? That is what Rockefeller wanted to know. And, what he thought the country needed to know in order to successfully implement temperance.

Toward Liquor Control – An Engineer and a Lawyer Re-Write American Alcohol Laws

To answer his question, Rockefeller commissioned a report from two researchers who worked on social and public issues: Raymond Fosdick, a lawyer, and Albert Scott, an engineer. The approach was to be data-driven, so that recommendations could be practical and implementable, unbiased and well-balanced. The resulting study was entitled Toward Liquor Control. For their research, the authors undertook a sweeping survey: lessons learned from various governments in Europe as well as Canada and Russia; examination of the US experience prior to and during Prohibition; interviews of stakeholders including judges, clergy, social workers, and newspaper editors; discussions with industry representatives; and a review of current state legislations. Distilling all of this information down, they focused on practical methods.

Toward Liquor Control was published toward the end of 1933, prior to the final state ratifying the 21st Amendment: right in the middle of the states’ dilemma of what to do with their newly acquired power. It, by default, became the resource that state legislatures could look to for a systematic understanding of how to regulate alcohol beverage commerce. Its appeal – in addition to being the sole resource available – was a clear, authoritative voice that proposed implementable actions.

‘Toward Liquor Control’ was republished in 2011 with this Introduction.

Fosdick and Scott’s Toward Liquor Control has done more to shape modern American alcohol policy than any other book except the Bible.

The Invention of the Authoritarian Plan and Control States

Fosdick and Scott believed that the best way to balance societal welfare with alcohol availability was for government to directly oversee alcohol sales, what they referred to as the authoritarian plan and what today are known as “control” states. A government’s monopoly on the sale of alcohol was not a new concept and its successful implementation could be seen in Europe, particularly Sweden. Additionally, the idea of state-level control was appealing as not everyone was ready to abandon Prohibition. By the end of 1933 five states had adopted a monopoly system of alcohol distribution, by 1935 the number had risen to fifteen, and by 1966 three more states converted making the total number of control states 18. In non-control states, local option laws allowed individual counties to regulate alcohol sales, in some cases banning it altogether, thus creating a patchwork of public access.

Part of the rationale for government monopolies is the ability to limit consumption through restricted access and increased pricing. To this day, control states have fewer retail outlets than non-control states, although many of the “blue laws” – restrictions on when stores can operate, such as Sundays – are being systematically relaxed. But the primary mechanism of control is pricing: excise taxes do exactly this. It was widely held, as it is today, that the consumption of alcoholic beverages is not neutral to society. That is, drinking has a cost, be they medical costs associated with excess drinking or with today’s references, drunk driving, etc. The role of an excise tax is to adjust pricing in order to compensate for such external costs.

The Three Tier System

For states not wanting to develop a monopoly system, the recommendations were similar: adjust pricing and avoid incentivizing sales. The means to do this are slightly different. First, strict adherence to a three-tier system would avoid incentives of combining distribution and retail. Second, pricing could be controlled through taxation as well as the issuance of licenses. The cost of the license raises the costs of doing business, and the number of available licenses limits access.

Toward Liquor Control became the handbook for how states and local communities could balance the availability of alcohol and its perceived ills. It singlehandedly structured the U.S. alcohol-commerce landscape. And, not just at the highest levels but also down to the minutia, and everything in between. The conceptual distinction between different types of beverages in the U.S. – beer, wine and spirits – for regulation and tax purposes was born out of this work. Some recommendations, such as not making any alcohol available by the drink, were proposed but sensibly ignored; if the U.S. was going to repeal Prohibition, then people wanted places to imbibe together, outside of their homes.

An À-La-Carte Collection of Fractured, Convoluted and Complex Laws

The consequence of all of this is a U.S. regulatory landscape that is fractured, convoluted, and complex. Large brush-strokes were laid by Fosdick and Scott not though a government sponsored assessment, but through a private individual’s contracted research. The concessions necessary for repeal of the 18th amendment meant that individual states could implement temperance as they saw fit, often selecting various pieces out of Fosdick’s and Scott’s work. And the states themselves had to capitulate to local interests so that within a state local-option laws allowed municipalities to govern alcohol sales in manners which were more strict than the state. The result was a new experiment in alcohol control which replaced the failed experiment of Prohibition. It has made the U.S. alcohol beverage market unique in the world. And, by many accounts, has been a great success. While the diverse landscape can be complex – and annoying – it has created an incubator whereby small boutique brands, inherently local to start, can experiment, gain traction and grow. Something that is virtually impossible anywhere else in the world that does not have such a fractured system. In short, both the complications and resulting opportunities are inherently American.

Resource – 1 Rockefeller in the forward to: Fosdick, R. B. and A.L. Scott. 1933. Toward Liquor Control.

American Spirits Exchange is a national distributor and importer serving the alcoholic beverage industry including distilled spirits, wine and beer. Learn More Here…

If you would like more information about working with American Spirits Exchange Limited please contact Chelsea Washburn at 215-240-6020 or email at Grow@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com or visit the American Spirits Exchange Ltd. website here.

Ready to Get Started?

Let American Spirits Exchange Ltd. Experts Help Grow Your Distilled Spirits Business

Our mission as a national spirits importer and distributor is to help make artisan brands broadly available, promote exceptional beverages in the U.S. and educate consumers about the art and science of craft alcohol beverages.

Call: 215-240-6020

General Information | Grow@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com

Accounting | Accounting@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com

Purchase Order Submissions | PO@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com

International Sales & Export | International@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com

Shipping, Freight Forwarding & Logistics | Shipping@AmericanSpiritsLtd.com

What is BrandScape? BrandScape is a way for product and service suppliers to talk directly to our audience. If you would like to learn more about BrandScape, please email Info@DistilleryTrail.com.