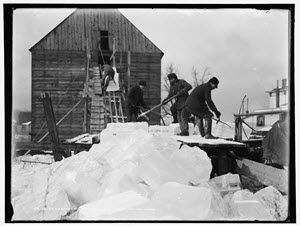

Shooting cakes into the ice house, c.1903. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Producing upwards of 8 million tons a year, the annual harvest in ice was more than just toil, but a harvest like any other. Seasonal shifts in temperature would define each annual yield relative to the depth and re-freeze rate of the ice. Along with a new industry, new techniques, tools and storage houses had to be developed if the competitive edge was to be retained.

Part 1: Ice Harvesting: Ice Wasn’t Always Cool

Part 2: Ice Harvesting: Storage, Techniques and Tools

To harvest ice, the first job was to obtain access to a lake frozen to a depth substantial for harvesting. The surface would then be marked out for the relevant sized “cakes” (American shipped ice cakes were around 22 inches square. Blocks destined for India or the West Indies were often a much larger size) before being deeply scored by a specialized horse drawn plow with metal teeth. Blacksmiths shod spiked shoes for horses while men wore corked soles to gain traction when on ice.

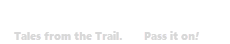

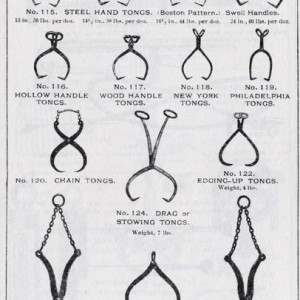

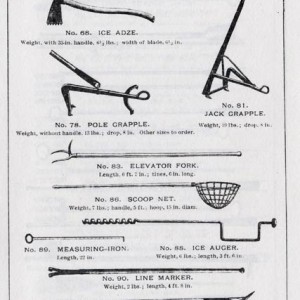

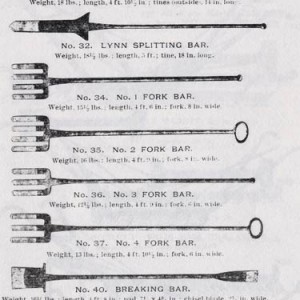

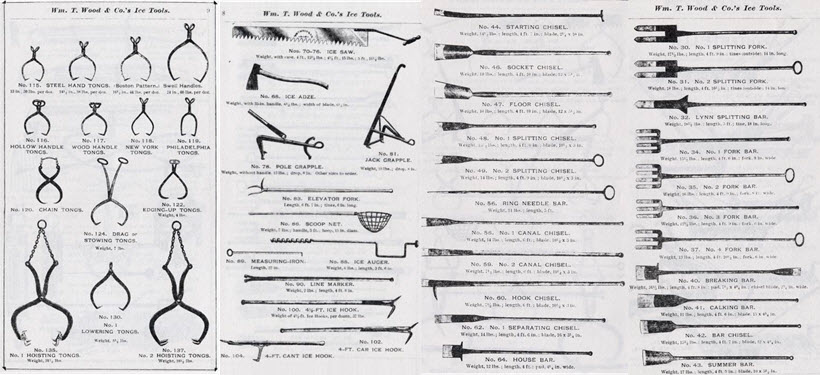

Once finished, these blocks could be prized apart by bespoke long handled picks, pry bars and chisels each designed relevant to the job required. A classic ice harvester’s arsenal was commonly comprised of such tools as the ice plow, ice saw, grapple, jack-grapple, breaking off bar, caulk-bar, packing chisel, house bar, fork bar, float hook and line maker, etc (see below). Once separated, these cakes would be manipulated with gaff hooks down predefined ice channels towards a mechanism which extracted the blocks and load either into an ice house for storage or a cart for transportation.

Click the Ice Tools images to see full size. Images courtesy of Library of Congress.

The ice house moves from below ground to above ground.

Despite centuries of subterranean ice houses having been built for the wealthy and privileged of Persia and China, a truly effective means of storage was not developed until ice harvesting’s founding father, Frederic Tudor, gave specific details of a building of his own design when first built in Havana, Cuba in 1807. The outer timber walls were 25 feet square with an interior of 19×16 feet. An upper floor sales room was built with a central trap door to gain access to the ice below and included a neighboring room as accommodation for the ice house keeper. The house was insulated by packed sawdust and peat and had a natural draining floor to carry away the melt water.

The most revolutionary element was its location above ground contrary to early Roman and Chinese ice house designs which were located below ground. Initial inspiration for this came from Frederic’s observations of Virginian ice boxes which were kept above ground in full light of the sun yet could, “keep their fish and meat fresh as in winter”.

A typical Tudor ice house was loaded from the top, stacking each piece upon one another until finally packed with sawdust for added insulation. A well made and packed house could retain the majority of its contents for several years with out replenishment, making it the most important tool in a harvesters trade.

Stay Informed: Sign up here for our Distillery Trail free email newsletter and be the first to get all the latest news, trends, job listings and events in your inbox.

Here’s a 1919 video of an Ice House in action. Your speakers still work, there is no audio.

Please help to support Distillery Trail. Sign up for our Newsletter, like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.